When we think that in a city like London there are so many little places where people gather for the feast and yet there are so many people who are in the street, in homes, in hostels, it is very painful. Probably none of you has experience of being in the street; I had it when I was a child and a youth, and it’s a very unpleasant feeling to know that you have nowhere to go and that you are totally unwanted in any of the places that shine with light, which obviously speak of warmth to you.

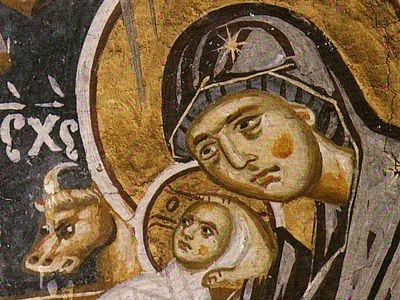

But this image is very much the image that we find in the first Christmas as described in the Gospel (obviously it was not called Christmas), because it was the night when God became man, and what do we see? We see Mary who is a expecting the Child Jesus, we see Joseph knocking at one door after the other in the hope that someone will give them shelter because She is about to give birth to a Child. And every door is slammed in their face because everyone on that night, as on every night, feels so comfortable and doesn’t want intruders, particularly the kind of intruders that will force them to pay attention to them in a very particular way. The only people who really kept Christmas the way most of us keep it, are the people who threw out Christ, the Mother of God and Joseph. And this is something to which we should give thought, because it is a very tragic image. And the only people who were Christmas itself, who were the incarnation of the Son of God, were thrown out into the darkness and found no other place for themselves except in a cave, or in a place where a few animals were kept. That is a direct hit at us. This must make us think. When we will be thinking of organizing our Christmas day, our Christmas evening, our Christmas night, bank holiday and so on, we will be doing exactly what these good people of Bethlehem did when they said, “We want to be cozy together, we want to be happy together, we want no intruder, we want no one to come and spoil the sense of being a family and our happiness. Other people can go elsewhere.” And “elsewhere” at times means nowhere—in this case the Lord and his Mother and Joseph found shelter together with an ass and an ox. And there was after a fashion a manger, that is, some straw prepared for them. That was all that the earth and the human community had to offer.

Now on that night something happened which is at the very heart of the Christian message—an event which is a fact of history in the eyes of the Christian that God became man, that God was born into this world. And it teaches us also something about God and about love, because the Incarnation, the fact that the Son of God became the Son of man, the Incarnation was an act of love. God entered into the world, to use words of the Scriptures, to save the world. And what does “save” mean? It means that the world was lost in the same way that a ship may be lost on the seas without oars, without rudder, tossed about; and this happened because the world through man and in man had lost its contact, its unity with God. The world was very much like a musical score from which the keys would have been cut out, unreadable, disorderly.

The Incarnation is something which moves me very much, because to me it speaks of the fact that God not only created a world, not only created it in an act of love in order to give Himself to it, but having given to the world freedom, which is the absolute, the unavoidable condition for a love relationship, He takes upon himself the consequences both of His act of creation and of the freedom and the misuse of freedom by man. He takes responsibility by entering into this world and taking upon Himself all the consequences of what freedom has brought into it—death, suffering, alienation from one another, alienation from Him, the dividedness which there exists within each of us between mind and heart, and will, and flesh. He takes it all upon Himself and bears the consequences by entering into this world, living in it and dying of it—of these consequences. A thing that strikes me is that in the night of Christmas we have a vision of God that we could not have ever invented. You know, the Old Testament saw God as the Holy One of Israel, as the unapproachable, unfathomable God, one who is light but light so bright, so blinding that when looked at he appears as darkness, as an unfathomable mystery. It was His greatness that evoked awe and at times terror. Ancient mythologies thought of gods as being the embodiment of all that one could desire, aim at; all the greatness and beauty which man could wish for. And here we find another image of God, something which no one could have invented or chosen because it would have been felt to be almost a blasphemy, an insult to God. We find a God who is frailty itself; an Infant, who is totally helpless, who is totally vulnerable, and for those who believe only in power, in strength, a God who cannot even be respected because He has no power to force upon people His authority.

This is perhaps the most beautiful image of love, of human love, of divine love that we can find; such readiness to give oneself to the other, defenseless, unprotected, ready to accept and endure anything for the sake of the beloved one. And then we see, we know from the Gospel that this was only the beginning, because this gift of self to a world distorted by hatred, greed, fear, and all other negative feelings and attitudes of mind, that the destiny of love in this world was to be rejected and ultimately rejected. When I think of Calvary, which is the other end of the destiny of the newborn Child, what I see in it is a cross and a crowd, a cross set up on a hill outside of the walls of the city because the people of the city had rejected Him utterly. He could not die within the walls, He was a stranger, He had no right even to die there. He had chosen to stand by God, and the people who were not prepared to take the same stand had no room for Him at all.

And then around Him is a crowd. On the Cross there was only sacrificial love and sacrificial silence, not a word of protest. Less than this or more than this—when He was crucified—Christ said, “Father, forgive them, they don’t know what they are doing.” At the foot of the cross are two persons—His Mother who was so at one with Him, in His gift of self, that She gave Him without a word of protest, silently dying His death as the mother alone can do; and the disciple, John, who loved Him so truly that He could accept His will to die rather than defend Him against His will, a love so great as to bring forth the beloved one as a sacrifice if He chose to be one. And then a crowd, a motley crowd. Among them are His enemies who mocked Him, who taunted Him, but also a much more complex crowd of people who were divided. Some hoped that at the last moment He would save Himself, come down from the cross as a victor and then they could without danger, without fear, believe in His message of love because love would not be the ultimate risk, love would not mean death, love would mean a passing fear and a certainty of safety afterwards. Some hoped that He would come down from the cross and therefore they could become His disciples without danger; others hoped He would not come down from the cross and that His monstrous, terrifying message of love could be discarded—a love that claimed the whole person, a love whose measure was the gift of self unreservedly.

And this is why on certain icons of the Incarnation, of Christmas in the Orthodox Church we find a cave with a dark black background, the classical scenery of Mary and Joseph, the two animals, the ox and the ass. But instead of a manger there is an altar—an altar built of stone on which the Child lies, because He is born onto death and onto the death of the cross.

This is, I believe, the message of Christmas that God so loved the world that He gave his Only-Begotten Son that the world may be saved, that the separation between God and man should be ended. And you may remember a passage from the Book of Job in which Job says, “Where is the man who will take his stand between my Judge and me?” And in one of the ancient manuscripts it says, “Who will put his hand on my shoulder and my Judge’s shoulder,” to hold us together, as it were, to bring us together, to prevent us from splitting, to unite us. And in the Incarnation, the fullness of humanity and the fullness of God abide within one Person, the Lord Jesus Christ. The two are confronted and the two are in harmony. In Him the harmony is restored, in Him God and man are at one again, and through Him this unity between God and man can be restored between humanity and God. This to me is the total meaning of Christmas—born, delivered by God unto death in helplessness; vulnerable, perfectly offered in an act of love, as love itself.

From a lecture given on December 3, 1986.