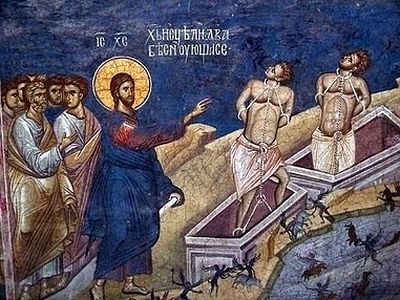

One of the powerful stories, narratives, in the gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, the so-called synoptic gospels, is this event when Jesus encounters this man who is in the region of the Gadarenes or there are different names—Girgesenes or Gerasene region—this man who is totally and completely possessed by demons, filled with all powers of demons. This particular event of the Gospel is read a couple of times in the Church year, probably because it’s so important that we would understand it. I heard, however, recently that once a group of priests were meeting, and someone asked, “What is the most difficult element in the Scripture to preach about?” The answer that the priests came up with, they thought it was this event about the possession of this insane man who lived in the tombs and how the demons get cast out of him into the swine.

Well, let’s think about this particular event. It’s virtually identical in Matthew, Mark, and Luke; almost in great detail it’s the same. There’re not many differences in the stories in the three different accounts, certainly not anything that would require us to make some particular comment, but what is the story, basically? This was just read recently in the Liturgy a few weeks ago. This time of year, the lectionaries are different in different Orthodox traditions, the Byzantine and the Slavonic, so I don’t know exactly when, but it was just read in the churches from the Gospel according to St. Luke, the version that is found in St. Luke’s gospel in the eighth chapter. So we’ll follow that one.

It says that Jesus was going with his disciples, and they arrived in the boat to the country of the Gerasenes (or the Girgesenes or the Gadarenes) which is opposite Galilee. It’s on the other side of Galilee. Then it says that when they came onto land, they met the man from the city who had demons, and this man was really, really demon-possessed; that he ran around naked, without clothing; that he didn’t live in the house but he lived among the tombs; that the people had tried to keep him seized and under guard with chains and bonds, and he would break them and he would come out and he would scare everybody, and they were all totally frightened of him, and he would be driven out of the city into the desert places. It was a man really, you could say, who was really spectacularly under the power of dark and evil powers and spirits, this possessed man.

When Jesus encounters this man, the demons inside him cry out, “What have you to do with me, Jesus, Son of the Most High God?” And that’s what it says in Mark; in Matthew, it says, “Son of God.” So he’s confessed as God’s Son. The demon or the demons in plural confess him as the very Son of God, the Son of the Most High God. “Why are you coming here to torment me?” So, of course, this clash between Jesus, the perfect, holy One of God, with this evil power; it’s a clash. So the evil is tormented by the presence of the good.

By the way, that’s what we think eternal hell will be. It’ll be people and creatures who are simply tormented by the presence of good; that when we are wicked and evil, and good is present, we are tortured. We can even just see that as an example. If one person loves another person, and that other person hates the one who loves him, the presence of that person will be a torment. You’ll try to get rid of the, you’ll hate them, you thrash against them; you’d like to kill them if you could, especially when that love is coming upon you and you don’t want that love; you don’t want to be loved, or you don’t want to know the truth. For example, if we’re living a lie, and someone comes who’s living in the truth, their presence torments us. So you have the same thing here happening with Jesus, the Son of God, [encountering] this violently, spectacularly possessed man, who is naked and crazy and breaking chains and terrifying the whole region.

So then you have this encounter that’s shown in Matthew and Mark and Luke, between Jesus and this man. Jesus says to him, “What’s your name?” And he asks that because he wants to hear the answer, and we have to hear the answer that the name is “Legion,” and it says, “Because many demons had entered into him.” Legion, many demons, a whole gathering. Here some commentators point out that Palestine at the time was occupied by the Roman soldiers, and there were legions all over the place, and the Jews considered these legions to be occupying powers, those who were captivating them, those who were holding them in control, and perhaps it was a way of speaking about their hatred towards the Romans, to give this name, Legion, to the demons who were holding this man. I don’t know if that’s so accurate, but it might be the case that that’s why this particular term is used. It might also be used because the angels are in choirs singing, but they are also in armies fighting, and the good armies are angelic hosts—hosts, that means armies; they’re the legions of God fighting against evil—but then the devils have their own legions, their own gatherings of evil spirits that destroy and attack and want to conquer.

But in any case, for whatever the reason, he says, “ ‘Legion,’ for many demons had entered into him.” There were many. Then it says they begged him, they begged Jesus, not to command and to depart into the abyss, and then there was a large herd of swine feeding on the hillside, and they begged him, Jesus, to let them enter into the swine. It says:

Jesus let them go, cast them out into the swine. The demons came out of the man, entered the swine, and the herd rushed down the steep bank into the lake, and they were drowned.

We have this spectacular image of this herd of swine, of pigs, all of a sudden becoming violently wild with these dark and ferocious powers that are in this man, and it’s obviously meant to show how destructive and how many and how countless and how powerful they were and what destructive power they had. So they go into these swine, who were probably just peacefully sitting around there, and all of a sudden these swine become totally crazy and wild with those very same demons, and they came rushing down the hill into the abyss and into the lake and they are drowned.

You really probably can’t have more of a spectacular imagery of the destructive power of evil than that. Those who are familiar with Russian literature know that the Russian writer Dostoyevsky wrote a book about people who were really possessed by destructive demonic powers, men who had become really wicked and evil and were just destructing nihilists who wanted to destroy everything. He named the title of that novel, Demons. In Russian, it’s called Bésy, Demons. In English that novel is usually titled The Possessed. In its original title in Russian it’s called Demons. But the epigraph of that book, in a little opening before the novel begins, this particular part of the Gospel is written there about these destructive powers of the evils going into these pigs, rushing down the abyss and perishing in the water.

We know and we see there—we should see—how ferocious and violent, spectacularly destructive is the power of the demons, and how that power was in that man, and how that man was completely and totally possessed. That’s the first thing that we have to see there. Here we can take this pericope, this particular event, this passage of the Gospel, and we can use it as a lens just to look at the life around us, because certainly in human life this same type of destructive evil, violent, spectacularly exists. You can see it, for example, even in people like Hitler and Stalin—God forgive me, but we have to name the names—these men who were so destructive, who could just put people in cattle cars and take them and put them in ovens and burn them and kill them or put people in prison camp or line them up and shoot them or bury them. We know that that kind of violent evil exists.

Then we can see it in society, of people who are just destructive, who just vandalize and destroy just for the sake of destroying, who don’t seem to have any element of reasonableness and purity and goodness in them, just cynical and destructive and can torture people. We know people torture animals. I heard on the radio recently how this gang of teenagers were caught who would just, just for no good reason, torture animals, torment them, burn them, skin them, do all kinds of awful things. Then we know that there are people—there are murderers, serial murderers. Our prisons are filled with people who are psychopaths, for whom the image of God seems to be totally obliterated.

In the Scripture of the New Testament in the Apocalyptic books like Jude and II Peter, they speak about people who are like waterless springs and clouds driven around and fruitless in any way, just creatures of instinct, it says, with nothing of God left in them. Well, that can be, and I think that we should honestly say that, yes, that’s the case. There is this spectacular, violent, purely evil, willful, destructive powers that we can actually see in various human beings; that people who just love darkness more than light, who just revel in debauchery, revel in destruction, rapacious, cynical, disobedient in any way, wanting no law whatsoever, and simply—possessed. Just possessed.

We could say, you know, people do ask; they’ll say, “Well, gee, are there really demons who do that? Maybe we just do that with our own will,” and so on. But here I think the Christian teaching would be: human beings never do anything purely by their own will. When their will is evil and destructive and they don’t want God’s will, then, really, that means that demons are in them; but when a person does want God’s will and says, “Let thy will be done,” and struggles to do what is good and true and beautiful, that means that the Holy Spirit is in them. In fact, St. Silouan said if we hate evil and struggle for good, even if we fall 70 times a day, but we get up again, that proves that the Holy Spirit is in us, that we are temples of God’s Spirit.

So there is always the law of God or the law of destruction in our human mind and heart. That would be a teaching of St. Paul in the letter to the Romans, very clearly, the seventh and eighth chapters. There’s always another law working in a human being. We’re never simply autonomous. So when people ask, “Was it me or was it the devil in me?” or “Was it me or was it the Holy Spirit in me, or Christ in me?” Sometimes people ask that. St. Paul says, “When I do good, I can do all things; not me, but Christ in me.” Well, is it he or is it Christ? Well, when it’s really him in his total freedom, the freedom given by the Holy Spirit, then it is Christ and then it is God. Then he’s a real human being and even can be honored and praised for his virtue. On the other hand, when a person is vicious, as opposed to virtuous, and just destructive, then the Apostle Paul would even say that’s not even the person that God made; that’s sin in them. That’s the devil in them. That’s evil in them.

But on the other hand, we also say that the possession of people very often can be somehow even against their will if they’re born in evil and raised in evil, and we don’t know about this man, how he was raised, why he ended up that way, what happened to him. But we would say, theologically, according to our understanding of things, he was probably raised in a whole culture of death, a whole culture of evil. Maybe—I don’t know—he had in him poisonous drugs and alcohol and God-knows-what, and his parents did, and produced that particular man. Nevertheless, deep down inside everyone, there is this possibility of choosing light and not darkness, of being delivered by Christ and wanting to be delivered. And it’s pretty clear that this man wanted to be delivered.

In any case, he was delivered. And then it says that there he was; and he was clothed, he was in his right mind, and he was sitting at the feet of Jesus. That particular expression, “clothed and in right mind,” that actually even comes from the Gospel. You know how we say, “How [are] you doing?” You say, “Well, I’m clothed and in my right mind.” Or: “How’s he doing?” “Well, clothed and in right mind.” Because when we’re naked and out of our mind, then we’re in the hands of the evil ones and are connected with that power that destroyed that herd of swine.

It says in this Gospel narrative that when the man was healed, the herdsmen who saw what had happened to the pigs, they fled and told in the city and in the country what had happened, and the people had come out to see what had happened. And they came to Jesus and they found the man from whom the demons had gone, sitting at the feet of Jesus, clothed, and in his right mind. Then it says a very interesting thing. It says, “They were afraid.” That they were afraid. They didn’t like what had happened. They didn’t know what was going on. They wondered, “How did this guy get healed? How is he now clothed and in his right mind? Why did all those pigs perish? What was that power that was in him that is not there any more?” So it says when they had seen it, those who had seen it told to everyone how he who had been possessed with the demons was now healed.

Then it says all the people of the surrounding country of the Gerasenes (or Gadarenes or Girgesenes or however it is), they came to see what happened. And then you have what John Chrysostom called, in commenting on this passage, a more vicious revelation of demonic possession. St. John Chrysostom said it was easy to see that that man in those tombs who was crazy and ferocious and broke chains and so on—it was pretty easy to see that he was possessed by dark and evil powers. But John Chrysostom says: but then we see something more subtle, more scary, much more frightening, and that is that the townspeople came and when they saw what happened and when they heard what happened, it said:

All the people of the surrounding country asked Jesus to depart from them, for they were seized with great fear. So Jesus got into the boat and returned.

So what happened? What happened was the people came and said to Jesus, “Get out of here. We don’t want you. We want our pigs. We want our life the way we know it. We’re ready to put up with crazy, mad people who are chained and running around crazy and naked. We can get used to that, but we know what we’re doing, and we don’t want you coming here, messing things up.” That’s pretty much how it has to be understood, at least according to Chrysostom, that we in this fallen world are so used to our crazy people, we’re used to our madness, but we want our pigs; we want our life; we want to do what we want to do. Therefore we don’t want Jesus.

So we say to God himself: “Please don’t come messing up our life. Don’t mess up the way we’ve learned how to live.” And, perhaps even most important, we say to God, “God, we want our pigs. We want our swine. We’re more interested in our swine and our kind of peaceful, prosperous life that we can live with crazy people. We don’t want this being changed,” so to speak. But isn’t it an amazing thing that they tell Jesus to go away? And Jesus, by the way, before he departs, according to the Gospel story, the man who was healed comes to him and says to him, “May I please go with you?” He begged him to go with [Jesus], and Jesus said, “No, return to your home, and declare how much God has done for you.” And then one interesting little point: it says in all three narratives, in Matthew, Mark, and Luke, that the man went home and went through the region and told to the whole city how much Jesus had done for him. See, Jesus says to him, “Go and tell what God has done for you,” and it says the man goes and tells everything that Jesus had done for him.

So he becomes a messenger of the deliverance from the power of evil in his own person. But what we have to see is there were other people who didn’t like that. They didn’t want Christ around. They didn’t want God bothering their life. And how many people there are like that now on the planet Earth, in our own country here of America. They want to live how they want to live, with their TV and their porneia and their greed and perhaps even their alcohol and their partying, you know, people say, “Let’s go partying tonight.” A total debauched life: sexuality, carnality, all kinds of stuff. And they don’t want God messing it up. They don’t want Jesus coming there and casting out those demons. They prefer the demons. They prefer the familiar demons.

The point is made, and Chrysostom makes it. He says: you know, the people who came and told Jesus to leave, they didn’t look like they were crazy at all. They didn’t look like they were mad. They didn’t look like they were insane. They didn’t look like they were demon-possessed. In fact, in modern terms, interpolating on what Chrysostom says in his commentary, We could actually say they were cosmeticized and deodorized and sanitized and nicely dressed, and they had combed their hair, and perhaps their women had put on their make-up, and they had their homes and they were going to eat their dinner, and they had their pigs and they had their peace, and of course there were crazy people running around, and they knew how to chain them up or how to put them in prison or how to kind of keep them under control, but they wanted their life. They didn’t want that healing.

Isn’t it an amazing thing that [it is] those upright citizens, you might call them, upright citizens of the city, leaders of the city, nicely dressed and nicely groomed. They come and say to Jesus, the Son of God: “Get out of here.” Jesus had said to the demons in that man, “Get out of here! Go in those pigs!” And he showed the violence of that power by the destruction of those pigs, but those people, that didn’t impress them. What they really wanted was what they wanted, and they wanted their life the way it was, and they didn’t want any Jesus Christ coming around and messing things up.

And isn’t it amazing that they tell him, “Go away”? So we have to think about that. You know, we’re probably clothed. We have jobs. Probably people think that we’re in our right mind. We go around, shopping and eating our dinner and watching the football game and buying our new car and taking care of our pigs and worrying about the economy and wondering about our investment. Then of course, we know there are crazy people around who scare us to death, and usually we don’t go where they live, and we want them to be kept under control by the cops or whatever, and maybe put in prison or something, but we’re kind of used to it, and we’re satisfied with it, and that’s what we want. We don’t want anything else; we don’t want anything anymore. Even if God Almighty would come and heal all the peoples and all the scary parts of our towns and neighborhoods, we’d probably says, “Listen: get out of here, especially if you’re going to destroy our pigs, because we want our pigs!”

What we see is a much more subtle form of demonic possession, one that we ourselves may be caught into, one that doesn’t appear to be evil like that crazy man in the tombs, but in a sense is even crazier, even more insane. How [much] more insane can you get than to say to Jesus Christ, the Son of God, “Get out of here. We don’t want you messing up our life. We don’t want you in our city. We don’t want you in our region. Please go away”? So we see two forms of demonic possession in this narrative.

Here we want to go a little bit further beyond the biblical text, and that is to the writing of the Holy Fathers who say there’s even a third form of demonic possession that may even be more treacherous than the two forms that we see in this Gospel event: the madman in the tombs and the nice, well-groomed upright citizens telling Jesus, “Go away.” There can be something even more treacherous. What would that be? That would be, according to the Holy Fathers and the saints, those of us people who claim to be with Jesus, who claim to want Jesus, who really appear to be preachers and teachers of the commandments of God and the Gospel of God in Jesus Christ, but we really don’t really want God, either. We don’t want God either. We may like religion; we may like the role that we play in the Church; we may like, I don’t know, talking on Ancient Faith Radio; we may like listening to Ancient Faith Radio; we may even be priests, like I am, or monks, or nuns, or bishops, or patriarchs, or whatever, but according to the saints, there’s a subtle form of demonic temptation for us “Christian people” who claim to be Christians but in fact are mad.

We may be mad simply because, in fact, we claim to be Christians but we live a secular life and are much more interested in our pigs than we are in the healing of society and in the healing of crazy people and getting people out from under the power of demons and darkness, that we’re not interested in healing people; we’re interested in protecting our own life and keeping things the way we like them. “Better the way we had it.” We don’t want to change. Even in our churches, we don’t want to change. Many times our [own churches] are in fact churches, but they’re not inspired by the Holy Spirit; they’re inspired by demons.

The saints say this. They say this in so many words. St. Theophan the Recluse said: Why is it that some people who claim to be very religious, who are going to church all the time, who are readers and teachers and Sunday school teachers and priests and pastors and monks and nuns and bishops—why do we [not] get better instead of worse? Why are we more judgmental? Why are we more angry? Why are we more irritated? Why are we even sometimes secretly living carnal lives, caught by the flesh? Why is all that going on? And St. Theophan said: Because we don’t really want God. Our God is a consuming fire. We don’t really want Jesus coming in and telling us what to do. We want to use God. We want to use Jesus for our own purposes.

And then they go [on] to say that there are particular demonic temptations that attack religious people, people who claim to be Christians. What are those things? Well, lust of power, to have power over people; judgment of others, where we can condemn all those who are really “of the devil,” and we’ll say who those people are. I don’t know: drug addicts and, I don’t know, homosexuals or abortion people or whatever. So we attack everybody in sight, and think we’re better than them and attack them, rather than identifying with their misery and trying to help them and to help ourselves to find the healing that comes from Christ. We just judge everybody in sight. Sometimes we even lie about those people in order to get more money to our churches and to our movements, to our causes, like radio preachers and television preachers who ask money from people so they can spew their venom and make people feel good by hating everybody else that they think are inferior to them.

Then, of course, the saints say there’s not only lust of power and judgment of others, but then there’s legalism. We think that we can please God by keeping certain rules and regulations of an external nature, how much we fast or how long our services are, or are they done according to the proper rules and all that kind of thing, and then the devil has us. St. Ignatius Brianchaninov, he has chapters in his book, The Arena, outlining this point in detail. He says how the monks get caught by the devil. He says the devil makes them get interested in the external forms of their church services, or the devil makes them get interested in their handicrafts or in their farms or in their animals, or the devil makes them get interested in their possessions, how beautiful their monasteries are, how the mosaics and the icons are, and aren’t they better than the other people. Or the devil gets them to judge the other people, because they’re not as holy as they are.

Then the devil gets them to envy one another; jealousy is a huge one. You get jealous of what the other person has, and you want to have it, too. Then, of course, the ultimate are vanity and pride, that we just become proud people, proud of how Christian we are, proud of how good we are. And we don’t even realize how miserable and… This is even written about in the Apocalypse. You say, “I’m great, I’m needy, I have nothing, I am with God,” but you don’t know how miserable and wretched you really are.

So there is a type of demonic possession that is not violent and spectacular like that man in the tombs in the Gospel story, and it’s not so subtle and hidden like those secularized people of the village who just wanted their pigs and their peace and told Jesus, “Go away.” There’s a worse form, a form that attacks religious people, people who actually talk about God and Christ. It’s a more subtle form where those people are even themselves—ourselves… Let’s put it that way: We ourselves, we can ask our question: Are we really in this for God? Are we really in this for good? Are we really in this loving our enemies? Are we really in this being merciful to everyone that needs mercy? Are we really in this wanting to be healed and to help to be instruments of healing other people? Are we really in this for the sake of Christ and for the glory of God and for the good of our fellow creatures?

Or are we in it for something else? Vanity, pride, power, judgment of others, even possessions of a religious type. I don’t know: our big, beautiful churches, our wonderful icons and so on. This could also be demonic, and it’s the most subtle demon-possession that there is. There’s a name for it in the tradition. In Greek, that name is planē; in Slavonic, it’s prelest. Sometimes even that’s written in English-language books, “prelest: p-r-e-l-e-s-t,” which means we think we’re with God; we think we’re holy, but in fact we’re in the hands of the devil; in fact we’re serving demons and not God, because we’re serving our own ego and our own power and our own will and not the will of God.

How do you know if you’re in demonic possession? How do you know if you’re deceived? Well, you don’t know, really. Every day I should say to myself, “Maybe I’m in delusion. Maybe I think I’m great and I’m judging others and thinking and going on an ego trip by giving talks on the radio. But maybe this is not pure; maybe this is not from God.” But what can I do about it? What can you do about it? The only thing we can do is to pray to God and say, “O Lord, lead us not into temptation. Deliver us from the evil one.” That’s the end of the Lord’s prayer. We should say it a hundred times a day.

Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us. Lead us not into temptation. Deliver us from the evil one.

We have to say:

O God, do not let me fall into temptation. O God, let me do what I’m doing for your glory and the good of the neighbor. O God, let me have real love for real people, no matter who and how and what they are. Let me be your servant and not the servant of Satan. Let me be a child of light and not a child of darkness. Deliver me from the vain imaginations of my own mind.

We actually pray that way in the Thanksgiving prayer after holy Communion in our Church. In [the] Orthodox Church we pray every time we have Communion:

Let this communion be for the release of the captivity of my own imaginings. Let me not follow my own heart. Let me not follow my own will. Let me really be a creature of God.

And then we say that prayer, we spit on the devil, and we get on with our work. And we don’t keep going back and analyzing, and we certainly are not afraid. “Be not afraid.” We don’t have to be afraid that we’re in the hands of the devil. We should just work not to be, pray not to be, do everything we can not to be, and God in his grace will deliver us. Then our actions will be pure, and then we will not be insane; we will be sane. We will be clothed, we will be in our right mind, and we will want to follow Jesus. Then Jesus will say to us, “Go, and tell the great things that God has done for you.” Then hopefully, like that man in the Gospel, we will go, and we will tell all the great things that Jesus has done for us.

And he has delivered us from the power of the evil one. He has cast out the demons. When we were baptized, those demons were cast out. We can maintain our baptism. We can live in the Church. We can hear the word of God. We can go to the holy sacraments. We can receive the Body and Blood of Christ himself for the forgiveness of sins, the healing of soul and body, the attaining of everlasting life, and the victory over all the powers of darkness.

So we have to pray that way, but we have to work. We have to work and we have to trust God, but by faith and by grace we can be children of God and children of the light and not children of the demons or children of the darkness. But let us be delivered from every form of demonic possession: the violent, spectacular form, like that man in the tombs; the secularized forms, like those people who asked Jesus to go away; but also that really subtle, really delusional type that can attack even religious people who think that they are Christians.

O God, deliver us from every power of the devil. Deliver us from the evil one.