Icon of Venerable Werburgh of Mercia

Icon of Venerable Werburgh of Mercia

One of them was St. Werburgh (also spelt: Werburga), who was born in the mid-seventh century and reposed about 700 (or even as late as c. 710). She was the offspring of the royal line of the kingdom of Kent which produced many saints. Her mother was the holy Kentish princess Erminhild, and her grandmother on her mother’s side was the holy queen Seaxburh of Kent. The latter had many other saints in her very large family. St. Ermenhild married the prince and future King Wulfhere of Mercia, who at first was a pagan (his father, king Penda, was a cruel pagan who even killed two holy Christian kings), but under his wife’s influence converted to Christianity and became a pious ruler. Mercia was the largest early English kingdom and was situated mostly in the central part of England, which more or less corresponds with today’s Midlands region.

When St. Werburgh and the other children of Ermenhild were born, Mercia was still a newly-baptized kingdom. The birthplace of St. Werburgh may have been the little town of Stone in Staffordshire (in this town two brothers of Werburgh, Sts. Wulfhad and Ruffin, slain by their pagan relatives, were formerly venerated). The holy queen raised all her children in piety but Werburgh surpassed all of them even from her childhood. Researchers suppose that as a child she received instruction from St. Chad, the bishop and enlightener of Mercia. According to her Life written in the late eleventh century, St. Werburgh was humble, obedient and meek. Every day she helped her mother in all domestic work, spent most of her time in church, and knelt in secret prayer for hours in her room every day. With great joy this Mercian princess listened to sermons and instructions on spiritual life, refused all the joys and riches of this world, with all her heart wishing to devote all her life to the service of God in virginity and purity and the ministry of people.

Her father, King Wulfhere, died in 675 when Werburgh was very young. Then she was entrusted to the care of her great aunt, St. Etheldreda (Audrey), abbess of the double monastery of Ely in Cambridgeshire, whose fame had spread all over England. Later she moved to the convent of Minster-in-Sheppey in Kent, where she lived for some time together with her mother St. Ermenhild (who as a widow took the veil as well) and grandmother St. Seaxburh. During her years spent in these East Anglian and Kentish monasteries, young Werburgh familiarized herself with the traditions of family and monastic piety and holiness, which were passed on there from generation to generation. She absorbed the instructions of holy men and women from her relatives living in Kent, and all this experience played a great role in her future life, for she was destined to return and spread all these practices and traditions of holiness to her native Mercia.

According to her Life, St. Werburgh was very beautiful, and a very wealthy man sought her hand. But the saint adamantly refused marriage, choosing to take up the monastic life. So she took the veil and with all zeal started practicing the virtues of a strict Christian life, spending time in prayer, obedience, divine contemplation, humility, and repentance. In time she became Abbess of Minster-in-Sheppey and later, Abbess of Ely. She successfully ruled both convents despite her youth, but it did not last for long. As Werburgh was already very experienced in spiritual life and skilled in teaching, her uncle, the saintly king Ethelred of Mercia, asked her to take over three convents in Mercia and improve discipline there, bringing them the firm monastic traditions of Kent and East Anglia. The saintly lady humbly agreed to undertake this difficult task, accepting it as the will of God.

These were the monastic communities in Weedon (now the village of Weedon Bec in Northamptonshire), Hanbury (in Staffordshire) and Threekingham (in Lincolnshire)—though some scholars believe that the latter convent was situated in Trentham, today a suburb of the city of Stoke-on-Trent in north Staffordshire. Werburgh was a very able and wise abbess, famous for her discernment, prudence and meekness; at the same time, she had quite a strong character. Her abbacy over the convent sisters was not mere governance, but rather a real ministry based on love; all the nuns loved Werburgh for her motherly care for them and for her wise instructions. Her biographers wrote that Werburgh handed over the souls of sisters entrusted to her to Christ by her word and deed alike.

She attended church services every day, read the Psalter while kneeling for hours and shedding tears; often she stayed in the church long after matins (even till the afternoon), praying on her knees or in prostration. The saint never ate more than once a day and used to read with unearthly joy the lives of the desert fathers. For her a great joy was to bring others to spiritual perfection and knowledge of Christ’s love, and thus make them happy. She was always quick to go and cure sick children, to console and give advice to their parents, to inspire and give hope to those suffering, to find necessary words to the young for correct spiritual life.

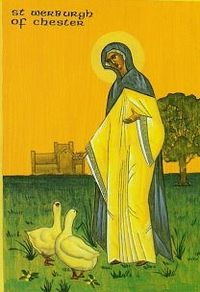

Stories of the life of Werburgh in that period abound with examples of her close communication with nature. Since time immemorial Werburgh has been venerated as patroness and protectress of geese. It was said that many wild geese spoiled crops in Weedon and neighboring fields. The abbess taught the birds not to do any harm to the crops, and they obeyed her. To this day some local people say that geese do not damage corn in the fields near Weedon Bec Once the geese dared to disobey her but the saint locked them in a stable as penance; however, this was an exception, as she greatly loved God’s creation.

Another time, the local steward complained to her about the wild geese and the abbess told him to lock them in a farmhouse. The steward called them together on her behalf and the birds obeyed. But the man yielded to a temptation: he caught and ate one, the fattest goose (a late legend says this goose was named Grayking and was Werburgh’s favourite goose). The next morning Werburgh called her geese but they started making a noise and did not move. She realized what crime the steward had committed—the abbess was known for her clairvoyance. She ordered him to bring her the bones of the geese he had eaten. The saint made a sign with her hand, and miraculously the bones were gradually covered with flesh, skin and feathers. Suddenly the whole bird was restored to life. All the birds then took wing high up in the sky, gladly nodding towards their abbess.

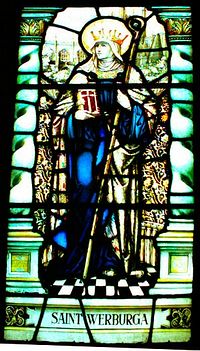

Since then the goose has become the St. Werburgh’s emblem. Geese inside a basket were depicted on pilgrims’ badges of St. Werburgh that were once distributed at her shrine. Actually, almost every popular saint in the Middle Ages in England had his or her own official emblem. Many churches in the Midland counties of England have stained glass windows depicting scenes from St. Werburgh’s life. It is known that holy shepherd Alnoth of Stowe was among the disciples of St. Werburgh.1 Once she even saved him from the cruelty of his master. St. Werburgh, who always radiated love for her neighbors, was beloved by everybody and already in her lifetime she worked miracles.

St. Werburgh reposed in the Lord in Threekingham, after many years of tireless and energetic labors for the glory of the Lord as abbess in Mercia. She predicted the day of her repose beforehand. Shortly before her repose she visited all her convents and gave respective instructions. The first uncovering of her holy relics, which turned out to be fully intact, occurred with participation of her brother, the righteous King Coenred of Mercia (Coenred was so impressed by his sister’s holiness that he himself decided to abdicate and end his life as a simple monk). Soon her relics were transferred to Hanbury, apparently by command of Werburgh herself (according to a later legend St. Werburgh reposed in Threekingham and asked to be buried in Hanbury. But the nuns refused to do this—they sealed the coffin with her body and kept watch. But at night all these nuns miraculously fell asleep, the bolts and bars opened by the power of angels, and the coffin was carried out of the convent by an invisible force and translated to Hanbury, while nobody knew about this at that time!).

Her relics, annually visited by thousands of pilgrims, remained in Hanbury till 875. When there was danger of Danish conquest, it was decided to translate them to Chester—now the county town of Cheshire in north-west England. Her relics remained incorrupt. The church where her relics rested in Chester was at first dedicated to Sts. Peter and Paul, but with time it was rededicated to St. Werburgh. St. Werburgh has been venerated as the patroness of this very picturesque former Roman town for already 1000 years, and due to her close link with the city the saint is often called “St. Werburgh of Chester”. In the ninth-tenth centuries the pious kings Alfred the Great, Aethelstan and Edgar the Peaceful as well as Queen Ethelfleda especially venerated this saint. In about 975 a monastery in honour of Sts. Werburgh and Oswald appeared in Chester—that was the “silver age of English Orthodoxy”. In the eleventh century, before the Norman Conquest, the pious earl Leofric and his wife Lady Godiva rebuilt the main monastery church in Chester out of their particular love for the saint.

In 1095, the relics of St. Werburgh were translated into a new more beautiful shrine in Chester. According to a historian of the eleventh century, St. Werburgh was among several old English saints whose relics remained absolutely intact (other such saints were Alphege, Cuthbert, Audrey, Edmund and Guthlac). There is considerable evidence that St. Werburgh healed many sick and more than once rescued the city from destruction by the Welsh, Danes and Scots. In 1180 a terrible fire broke out in Chester and the whole city was in danger. The monks of Chester took the relics of Werburgh and walked with them in procession around the city—and the fire stopped immediately. Countless pilgrims flocked to venerate St. Werburgh in Chester until the Reformation, and she remained one of the most venerated female saints of England.

In 1540, Henry VIII dissolved Chester monastery, the relics of St. Werburgh were probably destroyed and her shrine desecrated. However, the former huge monastery church was rededicated as a cathedral, though the name of Werburgh was then removed from its official dedication (today only a few old English cathedrals have dedications to local pre-schism saints—a sad sign of the Protestant legacy). This interesting and magnificent medieval cathedral, dedicated to Christ and the Mother of God, stands in Chester to this day and receives Orthodox, Catholic and Anglican pilgrims. Late in the nineteenth century, the pieces of the ancient shrine of Werburgh were reassembled and the splendid shrine was restored. Today it is displayed in the Lady Chapel of the Cathedral and, glory to God, is available for veneration.

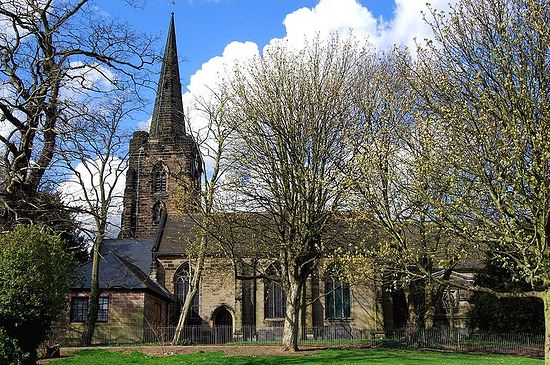

St. Werburgh's Church in Hanbury, Staffordshire

St. Werburgh's Church in Hanbury, Staffordshire

St. Werburgh's Church in Kingsley, Staffordshire

St. Werburgh's Church in Kingsley, Staffordshire

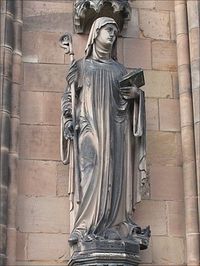

There are other links with Werburgh in the city: the street leading to the cathedral is called “St Werburgh’s Street,” and there is also a Catholic church of St. Werburgh in Chester. Today, as in medieval times, some young people, especially children and young women, ask for St. Werburgh’s intercession, and receive help from her. At least twelve historic Anglican churches and several Catholic churches are dedicated to St. Werburgh. And all the places where she labored for Christ still bear the memory of her. The ancient church in Hanbury, which also preserves two early English crosses, is dedicated to her to this day (it is possible that Werburgh actually established a convent here, while in Weedon and Threekingham she only restored monastic life). The parish church in Kingsley not far from Hanbury in Staffordshire is dedicated to her as well; there is a much-venerated statue of Werburgh inside the early English church of St. Chad (the apostle of Mercia) in the town of Stafford, Staffordshire.

The saint also labored much in Derbyshire, where churches in the city of Derby, as well as in the neighboring settlement of Spondon and the picturesque hamlet of Blackwell are dedicated to her to this day. Remarkably, the Spondon church has a ninth century cross and there is a holy well nearby. The Blackwell church has stood at least since the seventh century, though it was later rebuilt, and the present church also has an early English cross. The saint may have founded churches or small communities in all these places. The village Weedon Bec (the name “Weedon” means “temple hill”) has an ancient church in honour of Sts. Peter and Paul, situated on the site of Werburgh’s original convent: this church has a beautiful stained glass retelling her life. The village of Warburton in Greater Manchester is named after Werburgh. Notably, this village has two Anglican churches dedicated to Werburgh: “the old church” and “the new church”.

In early English times there was presumably a monastery on this spot. A modern Catholic church in the town of Birkenhead in Merseyside is dedicated to St. Werburgh. The site of the abbey of Werburgh in Threekingham is today marked by an ancient church, dedicated to St. Peter. In Kent there is a tiny peninsula called Hoo, which has a village of Hoo St. Werburgh—named in honour of the abbess who was celebrated here as well. An ancient local church there is dedicated to her. In early English times there may have been a monastery there that belonged to Peterborough. A whole district of the port city of Bristol in England is called St. Werburghs. One of the numerous parish churches of Bristol was dedicated to St. Werburgh; sadly, it was recently converted to secular use and holds no services.

There are several churches dedicated to St. Werburgh even in the southwest of England, which indicates that her relics may have travelled to various corners of the country for the veneration of the faithful. For example, churches in the picturesque villages of Wembury in Devon and Warbstow (“the holy place of Werburgh”) in Cornwall are dedicated to her. And, finally, an ancient church in Dublin, Ireland, standing on St. Werburgh’s Street, is dedicated to her as well. The main center of her veneration remains the Chester Cathedral. In icons St. Werburgh is usually depicted with a goose.

Holy Mother Werburgh, pray to God for us!