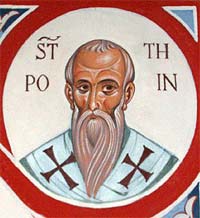

St. Pothinus

St. Pothinus

|

| St. Pothinus |

1. The beginnings of the Gallic Church

The Gallic Church had its beginnings in the first century. Western tradition holds that Gaul (France) was initially evangelized and baptized by St. Mary Magdalene, St. Lazarus the Four-Days Dead, and his sisters Sts. Mary and Martha. On the basis of St. Paul’s second Epistle to Timothy, several historians have thought that the Apostle Crescens, an envoy of St. Paul, labored in Gaul. Some also think that St. Paul stopped in Gaul on his way to Spain. In any event, Christianity penetrated into southern Gaul at an early date, specifically into Provence and the Rhone Valley — areas that had a strong presence of Greek minorities hailing from Asia Minor, Phrygia and Syria.

The written history of Orthodox Gaul begins in the second century with the Church of Lyons, which in the West was second only to Rome in authority and influence. Its first bishops were Sts. Pothinus and Irenaeus. St. Pothinus was among the Christians martyred by Emperor Marcus Aurelius in A.D. 177. Pothinus’ Acts, included by Eusebius of Caesarea in his Ecclesiastical History (Book 5, chapter 1), are considered some of the most beautiful writings of the ancient Church. St. Pothinus’ successor was the Hieromartyr Irenaeus, who had known the Hieromartyr Polycarp in his youth in Smyrna, the latter in turn having been a disciple of the Apostle and Evangelist John. The writings of St. Irenaeus of Lyons are numbered among those of the Holy Fathers of the Church; through them St. Irenaeus’ influence soon reached both Asia Minor and Egypt.

St. Irenaeus

St. Irenaeus

|

| St. Irenaeus |

Other cities also had martyrs and saints, even though persecutions were less intense in Gaul than in other regions of the Empire. The most venerated of these holy servants of Christ are St. Victor of Marseilles, St. Saturninus of Toulouse, St. Symphorian of Autun, Sts. Marcellus of Chalon-sur-Saone and Valerian of Tournus, St. Dionysius of Paris, St. Maurice of Agaune and the martyrs of the Theban Legion, St. Julian of Cenomanis (LeMans), St. Taurinus of Evereux and St. Patroclus of Troyes.

In the middle of the third century the Narbonne region and Celtic Gaul had more than thirty bishoprics. Local synods (councils) were held under the auspices of the Archbishop of Arles, and were attended by clergy from throughout Gaul and even from Britain. The number of bishops continued to increase until the end of the century, as the country painfully recovered from the Alemanni invasion of 257. Having been spared the persecution of Diocletian thanks to the moderation of Caesar Constantine Chlorus, the Church of Gaul was able to organize itself in peace even before the era of Caesar Constantine’s son, St. Constantine the Great. Still, on the eve of the 4th century, the Church in Gaul did not yet comprise a distinct “national Church,” as did the Churches of Antioch and Alexandria.

2. St. Martin of Tours and the flowering of monasticism in the West

Monasticism initially took root in the East, but at an early date the West received a model for this way of life in the personal example and writings of St. Athanasius of Alexandria, who lived in exile in Treves, Gaul, beginning in 335. Since Athanasius knew St. Anthony the Great and had found refuge among the monks of upper Egypt during a period of great danger, one can surmise that the Gauls heard at this time about the blessed Anthony and the ascetic exploits of the Egyptian monks.

In the 4th century the fire of Christianity began to burn fiercely in Orthodox Gaul. This was largely due to the example and inspiration of the growing monastic movement throughout the Christian world.

Two of the greatest saints of this time in Gaul were St. Hilary of Poitiers and St. Martin of Tours. St. Hilary, known as the “Athanasius of the West,” was the spiritual father of St. Martin. St. Martin is considered Gaul’s first great monastic saint. His example of “bloodless martyrdom” through asceticism was embraced by many.

Three important elements in the spread of the monastic ascetic ideal among the Gallic people can be described:

a.) The first true monastery was Marmoutier, founded by St. Martin. The monks in Marmoutier, who numbered eighty, all lived in tiny wooden cells built halfway into the natural caves on the side of an immense cliff along the banks of the Loire River. One can still see these caves near Tours. The monastery of Marmoutier had a strong influence, for many bishops were chosen from its enclosure. St. Sulpicius Severus speaks of monasticism there in his Life of St. Martin:

“No one there had anything which was called his own. It was not allowed to buy or to sell anything.…

No art was practiced there, except that of transcribers, and even this was assigned to the brethren of younger years, while the elders spent their time in prayer. Rarely did any one of them go beyond the cell. They all took food together.

Most of them were clothed in garments of camel’s hair. This must be thought the more remarkable, because many among them were such as are deemed of noble rank … and far differently brought up.” (Chapter 10 of St. Martin’s Life.) St. Martin’s particular expression of the monastic life at Marmoutier was naturally harmonious to the soul of the Gauls and served as a catalyst to the spread of Christianity among the people.

b.) One of the immediate spiritual fruits of St. Martin’s example was the famous monastery of Lerins. The founding of the monastery on the Isle of Lerins in 410 was the work of St. Honoratus, the future bishop of Arles. The monastery served as a spiritual school for bishops and ecclesiastical writers, such as St. Faustus of Riez, St. Eucherius of Lyons, St. Vincent of Lerins, St. Hilary and St. Caesarius of Arles, and St. Patrick of Ireland. The information that has come down to us about the life of the monastery of Lerins can be found primarily in the Life of its founder, St. Honoratus, and in St. Eucherius of Lyons’ In Praise of the Desert. From these sources one can see that most of the monks lived in community, while the more experienced struggled in an eremitic or partially eremitic way of life. Lerins-style monasticism (which held the anchoritic life in the desert as its highest ideal) spread throughout all of southeastern Gaul, notably in the Jura mountains with Sts. Romanus and Lupicinus, and in the Valais, where the monastery of St. Maurice of Agaune would remain an important spiritual center for centuries to come.

c.) Finally, the spiritual teachings of St. John Cassian must be mentioned. In 416 St. John founded the monastery of St. Victor in Marseilles. Prior to this in 400 he had been ordained to the diaconate by St. John Chrysostom. St. John Cassian was a great defender of the dogmatic teachings of the Church and carefully articulated the synergy between man’s free will and God’s grace. His primary labor, however, was to reveal to the Gallic monks the way of life and spirituality of the monks of the East. His Institutes and Conferences, which he wrote for the monks of Provence, are a glorious manifestation of the spiritual fruits he had acquired during his long stay in Egypt among its famous holy men. Many newly founded monastic communities, as well as ascetics who desired to lead the solitary life, used his writings as their spiritual manuals and guidebooks. The monastic rules spelled out in the Institutes were central to the foundation of subsequent monastic typica in the centuries to come, including the later Rule of St. Benedict.

(To be continued)