The Holy Right-believing Princess Anna of Kashin, a daughter of the Rostov prince Demetrius Borisovich, in 1294 became the wife of the holy Great Prince Michael Yaroslavich of Tver, who was murdered by the Mongol-Tatars of the Horde in 1318, (November 22). After the death of her husband, Anna withdrew into Tver’s Sophia monastery and accepted tonsure with the name Euphrosyne. Later, she transferred to the Kashin Dormition monastery, and became a schemanun with the name Anna. She fell asleep in the Lord on October 2, 1338.

St Anna’s sons also imitated their father’s steadfast confession of faith in Christ. Demetrius Mikhailovich (“Dread Eyes”) was murdered at the Horde on September 15, 1325; and later, Alexander Mikhailovich, Prince of Tver, was murdered together with his son Theodore on October 29, 1339.

Miracles at St Anna’s grave began in 1611, during the siege of Kashin by Polish and Lithuanian forces. There was also a great fire in the city which died down without doing much damage. The saint, dressed in the monastic schema, appeared to Gerasimus, a gravely ill warden of the Dormition cathedral. She promised that he would recover, but complained, “People show no respect for my tomb. They ignore it and my memory! Do you not know that I am supplicating the Lord and His Mother to deliver the city from the foe, and that you be spared many hardships and evils?” She ordered him to tell the clergy to look after her tomb, and to light a candle there before the icon of Christ Not-Made-By-Hands.

At the Council of 1649 it was decided to uncover her relics for general veneration and to glorify the holy Princess Anna as a saint. But in 1677 Patriarch Joachim proposed to the Moscow Council that her veneration throughout Russia should be discontinued because of the Old Believers Schism, which made use of the name of St Anna of Kashin for its own purposes. When she was buried her hand had been positioned to make the Sign of the Cross with two fingers, rather than three. However, the memory of St Anna, who had received a crown of glory from Christ, could not be erased by decree. People continued to love and venerate her, and many miracles took place at her tomb.

On June 12, 1909 her second glorification took place, and her universally observed Feast day was established. Her Life describes her as a model of spiritual beauty and chastity, and an example to future generations. (From OCA.org)

Chapter 1 of a contemporary Life of St. Anna of Kashin gives us a description of her home town of Rostov, and what life was like in the Russian lands during her childhood--the turbulent era of the Mongol Yoke.

Anna, Princess of Rostov

The Right-believing Princess Anna of Kashin was born Princess of Rostov, the daughter of Dimitry Borisovich of Rostov (†1294). There is no information about her childhood or youth in the Chronicles. They do not even give us her date of birth (nor that of her two sisters), but mention only the year of her brother Michael’s birth (1286), who apparently died in infanthood.[1] We can resort to an approximate estimation; if the chronicles refer to her marriage to Michael of Tver around 1294, and we know that maidens were given in marriage at an age not older than 17, then Anna must have been born in 1278 or 1279.

We know nothing about her mother—neither her name, nor where she came from. She is mentioned neither in the chronicles, nor in the genealogies, nor even in St. Anna’s Life. In the chronicles of Nikon for 1276 there is only a laconic mention that Dimitry Borisovich was married; later it was mentioned that he and his brother Constantine, together with their respective wives, went to the Horde, where the tsar “received them with honor.” The exclusion of information on Anna’s family should not confuse us. In those days, family information bore an only secondary significance—the most important thing was genealogical influence. This genealogy created and formed a person’s soul, lead him in the cycle of everyday affairs, conditioned his behavior, in much the same way as society forms a person in our day. The chronicles and oral traditions preserved the characteristic psychological traits of the thirteenth century Rostov princes, reflected the circumstances that Anna and her family experienced, and fixed in print the way of life in Rostov during that epoch. This data re-creates the Rostov “bosom,” which nurtured and educated Anna—the historical background upon which her silhouette is outlined.

The Rostov princes were distinguished by their particular characteristics of soul, inherited from their proto-ancestor, Constantine, the first prince of Rostov (†1218[2]). The chronicles bestow a good deal of praise upon him. He was “Christ-loving and pious,” a zealous builder of churches, a respecter of “the priestly and monastic ranks,” well-read, a lover of enlightenment (it was during his reign that chronicles were first kept in the episcopal see), soft-hearted by nature, guileless, generous, and merciful. His death was bitterly mourned by the people as well as his widow, a typical ancient Russian “right-believing princess,” who received the tonsure over her husband’s coffin.

This pious couple was a strong Christian root of the Rostov branch of the tree of Rurich. A reflection of its virtuousness fell also upon the handsome and brave Vasilko. Vasilko’s grandsons, Boris (Anna’s grandfather) and Gleb, who ruled the land of Rostov[3] for forty years, resembled their grandfather by their soft-heartedness, yielding nature, and guilelessness. In everyday life this kind-heartedness expressed itself as peace-loving, taking care not to let others princes of the Rurich lineage draw them into their political exploits, and to make every effort to normalize relations with the terrible Horde. It’s true, that circumstances—very difficult ones—had an influence upon the Vasilok lineage. The murder of their father, Prince Vasilok; their maternal grandfather’s, Prince Michael Vsevolodovich of Chernigov’s (Vasilok was married to Maria Mikhailovna, the daughter of Prince Michael Vsevolodovich) perishing among the Horde in 1246 because he did not want to fulfill the Khan’s orders to worship fire, the bush and the vale. This cruel execution took place in the presence of the elder Vasilkovich brother, fifteen-year-old prince Boris, who had come with his boyars to pay his respects to the Khan. This gruesome spectacle (the Khan ordered that Michael be executed not by the sword, but by beating[4]); the fear that his grandfather’s open and implacable enmity towards the Horde might instill a vengeful suspicion towards the two living Rostov princes; their irreconcilable position…. All these events and conclusions decided the Vasilkovich brothers’ external politics, their resolve to orient themselves in the Horde’s direction and their expression of willingness to live peacefully with the Horde.

Modern reconstruction of Mongol Horde attack.

Modern reconstruction of Mongol Horde attack.

In 1249, Gleb Vasilkovich went to the Horde, to the new khan Sartak, to pay his respects. In 1250 Boris also hurried to do the same. Later, Gleb would come repeatedly to the Horde, either alone and bearing gifts, or with Alexander Nevsky and his brothers. In 1257 he was married to a Tatar princess (named Theodora in baptism). Alexander Nevsky was friends with the Vasilkovich brothers. Not only did he travel with them to the Horde, but he would later spend time with them in Rostov in 1249 and 1259. Apparently the Vasilkovich brothers attracted him by their support for his politics of endurance and loyalty with respect to the Horde.

During the 1252 uprising which took hold of several cities of the Vladmir-Suzdal region, the Vasilkovich brothers waited humbly, and in 1277 they responded to Khan Mengy-Timura’s call to participate in his Caucasus campaign against the Yasi, and thus hastened to the south. Their princesses and children accompanied them to the Horde, where Gleb, who was married to a Tatar princess, already had many close relatives.

Representatives of the Church did not condone a Tatar-oriented diplomacy, but they did allow for some measure of compliance with the Tatars.

The Rostov bishops Cyrill and St. Ignatius understood their princes’ desperate position. The land of Rostov, shaken to its very foundations, badly needed peaceful times in order to recover from its experiences; just the same, the hierarchs watched carefully that such compliance not turn into a betrayal of the Christian Faith. It was alright to marry a Tatar woman, but only under the condition that she receive holy baptism; it was allowed to cooperate with the enslavers, but under no circumstances must they overstep the bounds of religious morals. The Church’s judgment was reflected clearly and plainly in the “Tales of Tsarevich Peter of the Horde,” undoubtedly compiled amongst the religious princely circles. These tales give a perfect model for interrelations with yesterday’s enemies—only through faith in Christ, through holy baptism and a virtuous Christian life can an enemy become a friend, and the unfamiliar, familiar.

The Tartar Tsarevich Peter had left the Horde, received holy baptism in Rostov from Bishop Cyrill, fought the good fight of evangelistic virtues, and was made worthy of a vision of the holy Apostles Peter and Paul, who commanded him to build and church on that spot. With the bishop’s blessing he fulfilled this command, and later entered into a union of brotherly love with Boris Vasilkovich (they became “named brothers”). Bishop Ignatius, Cyrill’s successor, confirmed this holy union by a special ecclesiastical rite of brotherhood. The Tsarevich finished his days in Rostov as a close relative of Boris’ family, and the Prince’s children called him their father’s “brother,” or “uncle until old age.” “And Peter reposed (1290) in deep old age, and departed to God in the monastic rank, having loved Him…” says the Tale. The church has preserved the image of the foreigner who came to love Christ, and was therefore loved by Him, and has canonized the Tatar Prince. He is commemorated on June 30 (o.s.).

This tale bears witness to the lively discussion then taking place in Rostov at the time over the problem of the Christian’s relationship to the Mongols, to the high religious level of conscience at which this problem was addressed, and how strictly the holy hierarchs of the Church guarded the Christian Faith.

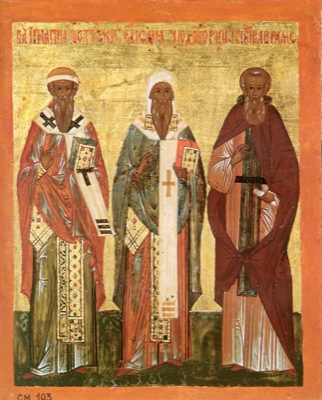

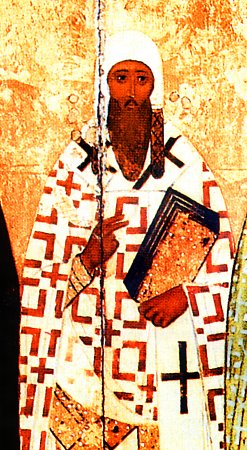

Holy Hierarch Ignatius and Isaiah, and St. Avraamy of Rostov.

Holy Hierarch Ignatius and Isaiah, and St. Avraamy of Rostov.

The Rostov princedom had long been a strongly religious land of glorious Church tradition, which it inherited from the outstanding hierarchs of the tenth through twelfth centuries: Holy Hierarchs Leontius and Isaac, and St. Avraamy, the enlighteners of the pagans of north-eastern Russia, and from Bishops Luke and Pachomius, exemplary instructors and archpastors.

After Battei Khan, under Bishop Cyril (1231-1262), a holy hierarch like unto the Kievan hierarchs before Tatar conquest; and under Bishop Ignatius (1262-1286), an ascetic struggler of the Kiev-Caves monastic type, religious life in Rostov was once again revived. Churches were built, monasteries founded, churches richly adorned with icons, frescoes, and precious vessels, all of which bore the mark of artistic good taste. It was said that the cathedral under Bishop Cyril was magnificent, adorned with gold, pearls, and precious stones “like a bride,” and the choir sang “mellifluously,” in Russian on the right cliros, in Greek on the left. It is recalled that under Bishop Ignatius work began on the “Rostov Theotokos,” that is, the Dormition Cathedral, to “cover Her roof with tin, and her floor with marble.” In the Chronicles it is noted that Prince Gleb “built many churches and adorned them with icons and books.

Book archives began to appear in monasteries, the Greek language was studied, literature in Russian and translation was collected, and the monks began to create some literature of their own—chronicles, saints’ lives, histories.

It would be an exaggeration to suppose that the cultural achievements in Rostov after Batei were of great significance. It is important only that these things existed, however modest they may have been in scale. Batei conquered the land of Rostov, but he did not pillage it, and thus the Rostov princedom recovered earlier than the others. Now in this north-eastern corner they were collecting, hoarding, preserving and hiding, diligently writing and copying, studying and teaching from this literature. Thanks to this conscientious dedication to literature St. Stephan of Perm could say that he received the tonsure in the Rostov St. John the Forerunner Monastery “because there were many books there.” The Rostov princes’ love of peace saved them, and protected the populace from disaster as well. In the Holy Trinity Chronicles of 1278 is written that Prince Gleb “served the Tatars from his youth…and delivered many Christians from the heathen.” The people of Rostov almost never experienced until the end of the 18th century the massive Tatar pillaging carried out under the guise of punishments which other cities such as Riazan, Kursk, Moscow, Vladimir, Peryaslavl, and Suzdal experienced during the latter half of the century…. And if some villages suffered, it was only because they happened to be in the way of passing Tatar battalions.

The prolonged peace encouraged trade, agriculture, and migration of people from more unfortunate neighboring princedoms. The Rostov region also drew Tatars—merchants and tradesmen—who eagerly packed into Rostov and other towns. The local people endured them patiently, albeit squeamishly. A bitter illusion of peaceful coexistence was created. But at times this endurance came to an end. The tribute collectors’ pressure, the accompanying battalions’ profligacy, the Tatar immigrants’ audacious behavior…. The insults were numerous. In 1262, when people began to beat up the “besermeny” (tax-farmers), the people of Rostov also did not sit by calmly. Some serious disturbances broke out in Rostov in 1286 as well, but this was when Anna was young. We will speak of this later.

Distinguishing characteristics of the Rostov land created a particular mentality, or as they say, “climate,” to Rostov life; a peacefully disposed, pious, patient, guileless people conducted their customary affairs. True, this peaceful prosperity fostered political backwardness; it did not instill the knack to struggle for one’s own existence and interests with weapon in hand and cunning diplomacy. This all left its effect upon Rostov’s historical fate, for the city quickly lost its independence. On the other hand, it encouraged religiosity and a pious disposition, fostered love for the Church, spiritual enlightenment, the beauty of religious culture; and conditioned people to unfailingly observe the religious moral traditions of Holy Russia.

Peaceful, grand Rostov was able to become a cradle of sanctity in a brigandous, warlike epoch. It is no coincidence that Rostov was the earthly homeland of many Russian saints, and many founders of monasteries along and beyond the Volga River came from Rostov.

Such was the bright heartland where Anna grew amongst the traditions strong Orthodox Faith, love for the Church, respect for the clergy and monastic rank, in awe of her relatives martyred for the Faith. As a child Anna undoubtedly heard about her ancestors who perished under Batei, and bore impressed upon her memory the image of her grandfather, the staunch Vasilko, and his sepulcher in the city’s cathedral. Undoubtedly she was awed by great uncle, martyred Prince Michael of Chernigov, revered his daughter, St. Euphrosyne of Suzdal. And of course she would have heard from her father of the prince Roman Olegovich of Ryazan, the passion-bearer and confessor (†1279), who died under terrible tortures in the Horde. Anna’s father was only 17 years old when Roman Olegovich[5] died, and all the Russian people were stunned by this holy prince’s struggle.

These examples of “passion” for the Faith, for truth, and sanctity touched also Anna’s young soul. It seems that providence even then began to prepare her for suffering, disturbing her heart and soul with images of tortured princes.

The mystery of sanctity also touched Anna’s soul at an early age.

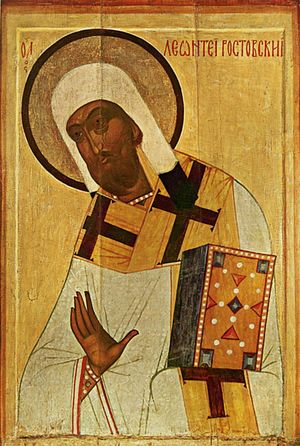

St. Ignatius of Rostov.

St. Ignatius of Rostov.

By his living example, Bishop Ignatius, taught Anna firmness of unwavering faith, and prepared her to become a confessor. Anna was ten or eleven years old when this austere ascetic reposed (†1288), and miracles began to occur during his funeral that shook all of Rostov. He is commemorated on May 28.

For many years Dimitry Borisovich’s family was close to the Tsarevich Peter, the righteous Tatar elder, for whom faith in Christ had become the meaning of life. Anna’s grandfather loved him as a brother, and he was her father’s “uncle.” He finished his days in Rostov in 1290, when Anna was twelve or thirteen years old. Couldn’t these religious impressions of her childhood have fostered the love of virtue, which adorned her Life?[7]

Her Life emphasized her piety, high morals, good upbringing in the fear of God, the keeping of His commandments, compassion for the impoverished, orphaned and hapless. It also notes her labors of prayer and asceticism, her rejection of “comfort and sweet foods,” “unceasing prayer and insatiable desire for God,” complete submission to God’s will, zeal for all things pleasing to God, meekness, and total unfamiliarity with any vain stubbornness or self-justification. Anna was “imbued with the teachings of divine words,” and “therefore she was accustomed to spiritual joys, and paid no attention to the beauty of this age, for it is delusion…” These were the usual characteristics of ancient Russian righteous women, surrounded by the spirit of monasticism.

It would be wrong to think that these were just “pretty words” about the Saint. We know for a fact that just such characteristics of ideal spiritual beauty were to be found in this righteous woman of ancient Russia. Anna’s soul was like a precious diamond that shone forth a rainbow spectrum of Christian virtues, winning deserved praise from her people unto posterity. The people of ancient Russia, for whom her Life was written, could have delighted in only this type or example of femininity.

If we follow Anna’s life during the period of her father’s reign (1278-1294) according to oblique references in the chronicles, we note a few particular events.

Dimitry Borisovich, Anna’s father, was by nature an exception amongst his relations. Restless, obstinate, difficult to get along with, he got into fights for various reasons, first with his cousin, when he “took some territory from Michael Glebovich with sin and great unrighteousness,” as the Voskrensensky chronicles for 1279 state; and then two year later with his own brother, Constantine, when “the devil instigated enmity and sedition between the brothers.” Apparently Dimitry Borisovich did not care for a dual reign with his brother Constantine. If Bishop Ignatius had not made peace between them, it might have ended in military conflict.

Neither did he care for Rostovian political passivity, so he made an attempt to depart from its neutrality. When Alexander Nevsky’s three sons, Dimitry, Andrei and Daniel plotted a campaign against Tver, Dimitry Borisovich joined them. He wanted to weaken his strong, wealthy neighbor, and gain as much a possible for himself from Tver. The campaign was carried out, but did not develop into a war. In the chronicles of Nikon for 1288 it is noted, “The allies marched toward Kashin, and stayed outside of Kashin for nine days, and decimated everything; and they burned Kosniatin, and wanted to go forth from there to Tver. Prince Michael (17-year-old Michael Yaroslavovich, Anna’s future husband) went forth against them with his forces, and thus began negotiations with them, and having made a peace treaty, all departed.” Dimitry Borisovich gained nothing from the campaign.

He had not yet returned to Rostov when a great disorder broke out there… There were sudden, elemental conflicts of unknown origin: the citizens struck the town bells and began an attack upon the Tatar homes and businesses, running all the Tatars out of town. This was not a revolt against the hated authorities, but rather disorder and popular protest against its representative’s abuse. The Princes ran to the Horde to beg mercy of the Khan. The chronicles of Nikon for 1289 note that Anna’s father and his brother Constantine, together with their wives (Constantine was married to a Tatar woman) left for the Horde. Anna and her sisters were left to the care of their relatives and nobles. No one knew whether they would return having made peace, and, if they should return, with what information—would the Khan punish the people of Rostov with a merciless pogrom, or would he forgive them? Apparently their marital connections with the Horde helped them out, and all turned out well, but this experience could not but have left a deep mark upon Anna’s memory. She was twelve years old at the time. At that age the significance of events might slip by, but the events themselves make an impression upon the consciousness. It is possible that she felt what the people around her were going through during those torturous days. And many more times did Anna have to expect what seemed to be an unavoidable catastrophe—the wreaking of vengeance.

The second attack on Tver in 1290 was a complete failure for Dimitry Borisovich. The people of Novgorod had a disagreement with the people of Tver, and persuaded Dimitry Borisovich to take sides with him. He gathered an army and invaded the borders of Tver, but before he ever connected with the Novgorodians, they had already concluded peace with Michael Yaroslavovich of Tver. Thus Dimitry Borisovich returned empty handed.

His diplomacy was fatally unsuccessful.

In 1923 there was a disagreement between the sons of Alexander Nevsky, Andrei and Dimitry, over the grand principality of Vladimir. There had been rumors spread around the Horde accusing Dimitry of treachery, and secret discussions with the Khan’s enemy, Khan Nogai. Dimitry Borisovich, together with his brother and nephew, Prince Theodore Rostislavovich Yaroslavsky,[8] took Andrei’s side. The princes went together to the Horde. The people of Rostov made use of their connections and supported Andrei with a strong army. Khan Tokhta decided to settle the matter—a decision that had disastrous consequences. The Khan’s brother, Tsarevich Diuden, began such a pogrom in north-eastern Russia that was reminiscent of the time of Batei. Vladimir and fourteen other cities suffered. The Tatars raided indiscriminately Dimitry’s allies as well as those only under suspicion, even Tohkta’s own supporters. Moscow was also hit. Prince Daniel, who supported his brother Andrei, trustingly allowed in the Tatars, who then looted the entire city. Other “innocent” towns also suffered: Mozhaisk of Smolensk, and Uglich of Rostovsk.[9] Only the principality of Tver did not suffer any raids. Tver had not participated in the coalition against Dimitry, but the people of Tver armed themselves just in case, and decided to defend themselves. Diuden, passing by Tver, headed for Novgorod. The people of Novgorod hastened to accept Andrei as their Grand Prince, and bought off Diuden. The Tsarevich went on his way.

The Grand Principality of Vladimir fell to Andrei, while Dimitry died in that same year, 1293 “in black garb” [that is, he received the monastic tonsure], in his pillaged, burned to ashes town of Peryaslavl. Thus did the civil strife between Russian princes come to end before the eyes of the Tatars.

Rostov, Andrei’s ally, remained out of immediate danger; only Uglich was harmed, but war nevertheless could not but disturb the peaceful flow of life in Rostov. Terrifying rumors, general commotion, anxious forebodings, not knowing what will happen next…. News came quickly that the Tatars were wreaking havoc in Vladimir, that the church of the Nativity of the Theotokos had been looted, and the beautiful brass floor in the cathedral was broken apart. Moscow was decimated, Uglich devasted, and the inhabitants of Peryaslavl had, to a man, fled before the Tatars could attack. Finally, threatening signs of nature added to the general catastrophe: thunder, sharp winds, fatal illnesses, and terrifying signs in the heavens. These are all noted in the chronicles for the year 1293.

The people of Rostov had barely come to their senses when Dimitry Borisovich died upon his return from the Horde.

The reign of this enterprising but rather uncircumspect man, who had strayed from the peace-loving course of his ancestors, brought no benefit to the land of Rostov. His conquests were unsuccessful, and his diplomatic service to Prince Andrei turned out to be not only useless, but even fatal to Rostov—by supporting the unlawful pretender to the Vladimir “throne” (Andrei was younger than Dimitry), he contributed to the strengthening of the Muscovite princes so decisively, that during the reign of Daniel’s son, Ivan Kalita, the Rostov principality came under Moscow’s heel.

Anna’s father’s repose marked the end of the Rostov period of her life. It is not known whether her mother was still alive in 1294, or Anna and her sister Vasilissa[10] were left orphans; in any case their fate was left in the hands of Constantine Borisovich. From subsequent notations it is seen that their uncle settled their fate that same year by giving them both in marriage. There apparently was no recognition of a mourning period in those times. The chronological wedding dates often show the haste with which widowed princes entered into a second marriage. Apparently their father’s repose did not prevent the betrothal process from beginning for the orphaned daughters.

Anna was betrothed to Michael of Tver, while Vasilissa was betrothed to the “conqueror” himself, Grand Prince Andrei. Both sisters were the daughters of Rostov princes, and were considered “good matches.” These were diplomatic marriages

The restless Dimitry Borisovich had twice invaded the borders of Tver. Thus, forming a family relationship with the Rostov reigning house meant for Prince Michael the establishment of good relations with his neighbor.

Vasilissa’s marriage was an answer to Rostov’s traditional political tendency to live in peace with the Horde, and to maintain good relations with the princes whose power was upheld by the Tatars. This was the case with Grand Prince Andrei.

We have very little record of the details of Anna’s wedding. There can be no thought of even a hint of romance between the bride and bridegroom. Pushkin’s lines in Eugene Onegin

“…Tell me, Nanny,

About your olden times,

Were you in love then?”

“Well enough, Tanya! In those

days,

We never heard of love…

“Then how did you marry,

Nanny?”

“I suppose it was as God

willed...”

could reflect the experience which, up until the beginning of the nineteenth century, was preserved in the depths of the life of the people, and was the inheritance of all Russian girls.

Her Life recalls that Michael’s mother, Princess Xenia, sent emissaries of betrothal to Rostov, having heard about the beauty and virtues of the bride, and that Anna was brought to Tver, where the wedding took place.

There is a detailed description of the ancient Russian royal wedding of the daughter of Vsevolod “of the great nest” of Verkheslavy in 1189 with Rostislav Rurichevich of Belgorod. We can assume that the wedding ceremony, for the most part, was the same 100 years later.

After the agreement between the emissaries of betrothal was concluded began the leave-taking of Verkhuslavy. The princely families and neighbors came together. The bride was bestowed with pearls, precious stones, and articles of gold and silver. The bridegroom’s emissaries, their wives, and accompanying boyars were generously bestowed with gifts. Gifts were sent with them to the future father-in-law. Not only relatives, but even fathers of the city gave gifts to the bride. Feasting and merriment went on in the future father-in-law’s house for two weeks prior to the wedding. Then came the solemn moment—the bride’s departure. Surrounded by all the guests and townspeople, the bride was placed upon a steed, and her mother and father, together with all the court, conducted her to the third stopping point. There the parents departed from her and she was accompanied further by her brother, with her father’s boyars and their wives. After six days the wedding train arrived in Belgorod. The bride and bridegroom were wed the same day, and the entire town held a three-day feast.

It is unlikely that Anna’s wedding was so festive and pompous. Extended holiday with noisy feasting would have been untimely in Rostov after the recent horrors of pogroms, and the bride’s father repose….

What could Anna have heard about her bridegroom? Her father had gone against him twice with his forces. She might have heard her father tell of the young prince, that he was decisive, courageous and enterprising, of warlike and independent character. This temperamental, willful prince of Tver displayed rare courage at Diuden’s rampage. He was the only prince who resolved to defend Tver, while all the others, frightened by the enemy’s forces, opened the way for Diuden to enter there cities without a fight.

Anna could have heard her father’s accounts of Micheal’s appearance, perhaps as he was described in the chronicles of Nikon: “very large of body and strong, manly and with a terrifying gaze.”

Sts. Michael of Tver and Anna of Kashin.

Sts. Michael of Tver and Anna of Kashin.

She undoubtedly knew that her future husband was the only son of his mother, the widowed Princess Xenia; that her future mother-in-law was pious and intelligent, that after the death of her stepson, Sviatoslav she reigned in Tver under the direction of the boyars, since Michael was still too young. She also knew that one of her future husband’s sisters was married to Yuri of Volhynia, and the other had received the monastic tonsure three years ago.

Anna arrived in Tver on November 8, 1294, the feast of the Archangel Michael, her bridegroom’s name day. She was accompanied by the Rostov boyars to the station, where they were met by the boyars of Tver and taken to the cathedral, where Micheal beheld his bride for the first time.

We do not know what Anna’s outward appearance was like. Her icon from the seventeenth century depicts her as an eldress of sad countenance, with a prayer rope in her hand. On an older icon from the monastery of the Meeting in Kashin she is shown as young, full stature, with an eight-pointed cross and prayer rope in her raised right arm, and a branch in her left. In a fresco from the end of the nineteenth century, in the Theophany-St. Anastasia monastery in Kostroma the artist depicts her as the Princess of Tver—wearing a crown and veil, with royal attire, and the winsomeness of tender youth. Her right, blessing hand, the cause of such tremendous confusion in the seventeenth century,[11] gives no cause for disagreement—in the blessed land of the saints there is no place for such in-fighting.

The wedding ceremony was performed by His Eminence Andrei,[12] the second bishop of the Tver diocese, newly formed in the 1270’s. Princess Xenia blessed the newlyweds with an icon of the Savior. “And there was great rejoicing in Tver,” (the usual chronicles formula for princely success and festivity).

The people of Kashin marked this event with the building of the church of the Archangel Michael and the triumphal St. Michael’s gate from the Kremlin to the Tver Road. In the Dormition cathedral there was a festal service, and the clergy processed with the cross to the parishioners’ houses.