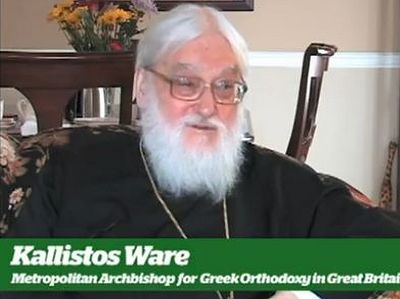

Conducted by Deacon Andrei Psarev

Oxford June 3, 2013,

This interview is an expansion of Deacon Andrei Psarev’s article “Metropolitan Kallistos Ware of Diokleia and the Russian Church Abroad.”

Your Grace! When was your first encounter with the Russian Church Abroad? Maybe you could start with the year that you discovered the Russian emigre church in London.

Yes. Well, let’s go back to that. I first entered the Russian church of St. Philip’s in Buckingham Palace Road in the year 1952, when I was seventeen years old. I was still at school (the English sense of “school,” which does not mean university). It was my last year at Westminster School in London, just before I entered the University here in Oxford. I have described the impression made upon me by the Vigil service in an article that was reprinted in my book The Inner Kingdom. Perhaps you have that book. If you don’t have a copy, I can give you a copy.

Now the church at Buckingham Palace Road belonged to the Anglicans. It was given to the use of the Orthodox in 1924, after the closure of the Russian Embassy Chapel, which, until then, the Russians had as their only place of worship, in Wellbeck Street. But when Britain gave diplomatic recognition to the Soviet Union, then of course the former Russian Imperial embassy had to be vacated, and so the Anglicans offered a church in central London. It was offered in 1924 simply to the Russian Community, which was at that time still ecclesiastically united.

Then, in 1926, there came the split between the followers of Metropolitan Evlogy in Paris (who later, in 1931, went under Constantinople) and the people who adhered to the Karlovtsy Synod. There was a curious arrangement. One Sunday the Karlovtsy group used the church, and the next Sunday the Evlogy group used the church. So, they alternated, Sunday by Sunday. They had special arrangements as to who should use the church in Holy Week and at Great Feasts. That continued until about 1945, when the Evlogy parish went under the Moscow Patriarchate. That, I think, made the sharing much more difficult because between the Paris Russians and the Zarubezhnaya Tserkov there was no very close contact, although they, at least in some sense, recognized each other.

I think a lot of the congregation didn’t mind which jurisdiction it was. They just went to the church because it was a Russian church. But, technically, they did alternate. When I went in 1952, I remember the first Vigil service. I wasn’t free on Sunday mornings — I went to the church in Westminster Abbey. The first Saturday evening, there were two priests with white, long beards, and a deacon. The next Saturday evening there was only one priest, who had no beard. And then the next Saturday evening the two priests with long beards and the deacon were back again. I didn’t understand the reason for this alternation until years later. But the priest with no beard at all was the future Metropolitan Antony (Bloom), who at that time didn’t have a beard, and was the priest of the Moscow parish.

Nikolai Mikhailovich Zernov

Nikolai Mikhailovich Zernov

The Russian parish in Oxford belonged to the Moscow Patriarchate. The parish priest was Archimandrite Nicholas Gibbs, who had been tutor to the Tsarevich and the other children of the last Tsar, Nicholas. Fr. Nicholas Gibbs had been ordained in the 1930?s by Metropolitan Nestor of Kamchatka. I think he was ordained, probably, in China. He had served, after the revolution, in the Chinese Customs Service. It was because of the connection with Fr. Nicholas that Metropolitan Nestor was invited over [to England] in 1938, and took part in particular services at the Anglican shrine in Walsingham.

Fr. Nicholas changed from belonging to the Karlovtsy jurisdicition to the Patriarchal church. I’m not sure of the exact date. But, when I talked with him about his, he said that, once they had elected a patriarch, he felt, “Now we have a patriarch in the Russian church — we should all be under him.” And so, I suppose that was about 1945. At that time the Russian Church was using a small chapel in Marstsen Street, in a house that Fr. Nicholas had acquired.

His assistant priest, who came in 1953 — that would have been a year after I had arrived in Oxford — was Hieromonk (later Archbishop) Vasily Krivoshein, who came from the Holy Mountain. So, in the 1950?s, in that way, I did meet a number of Russians who were here in Oxford, belonging to the old generation. Fr. Vasily Krivoshein would have been born in Russia and brought up there. His father was a government minister.

A very important Russian link for me was in 1957, when I met, for the first time, Mother Elizabeth (Ampenov), who was abbess of the woman’s community in London. She had come from Jerusalem, though she’d been brought up London. The nuns, of whom there were six at that time with her, were all Arab sisters who had been educated in the school at Bethany, run by the Russian Mission. I met Mother Elizabeth in January 1957. By this time I was seriously considering joining the Orthodox Church. The Greek Bishop — assistant Bishop — at that time, James, had discouraged me from joining the Orthodox Church. He said, “We are only really a church for emigres, for Greeks or for Russians, and there’s no place for an Englishman. You should stay in the Anglican Church. It is a very good church. We have good relations with the Anglicans. That’s were you have to be.” I was a bit distressed by this attitude. I went to see Mother Elizabeth, who was absolutely firm and clear. She didn’t speak against the Greeks, but she said: the Orthodox Church is the true Church of Christ. If you believe that, you should join the Orthodox Church. There’s no question! She was very definite. “But,” she said, “Our position in the Russian Church in Exile is difficult, because we do not have very easy relations with the other Orthodox.”

So, she advised me to go and see the Serbian priest in London, Fr. Miloj Nikolich. Fr. Nikolich said, “Of course you could become Orthodox with the Serbian Church, although we too have our problems. Though we are not divided into a Patriarchal and an Exile jurisdiction, yet we have difficult relations with the church in Yugoslavia under communist rule. You are English. You should not involve yourself in specifically Russian or Serbian problems because of communism.”

How interesting, Vladyka!

He said, “Better to go to the Greeks, because they can have a fairly normal relationship with their mother Church in Constantinople, and with the church in Greece. They do not have this problem of how to exist under communist rule.” I said, “I’ve been to see the Greek Bishop, and he told me to stay Anglican.”

“Oh!” said Fr. Miloj, “Did he tell you that? Go back and see him. Get in touch with him in a week’s time.” What Fr. Miloj Nikolich said to Bishop James I don’t know. But he clearly spoke to him in some rather definite way, because when I contacted him again he said, “Come and see me again, and we shall discuss the date of your reception.” So he changed his position completely, and he did receive me.

I would have preferred to join the Russian Church, because I felt very deeply drawn by Russian spirituality, by figures such as St. Seraphim of Sarov, in particular. He made a very strong impression on me.

But I knew Classical Greek, so it was easier in the Greek Church from that point of view. I realized also that it was a problem. I would have had to make a choice between the Karlovtsy jurisdiction and the Moscow Patriarchate. I did not want to join the Moscow Patriarchate. I never seriously considered that, because I could not feel happy about the compromises that the Russian Church in the Soviet Union had made with the communists. But I recognized that they were under persecution and I was not. It was not for me to judge them. But, at the same time, I felt that I could not be involved with the kind of statements of support that they made for the communist regime.

It is fair to say that Fr. (later Metropolitan) Antony did not, on the whole, make such statements. He remained quite independent. I don’t think that he ever went to the Soviet embassy. He was not a Soviet citizen. He was French citizen. He also, I was told, never accepted any money from Russia. At that time, the clergy of the Moscow Patriarchate in the West were, most of them, paid a stipend from Russia. They had to go to the Soviet embassy to collect their money. He never did that. So he kept a position of independence — of loyalty to the Moscow Patriarchate, but independence.

However, at a later time, he did criticize the priests Frs. Nikolai Eshliman and Gleb Yakunin, who wrote their letter to the Patriarch, I think, in 1966. He said they should not have criticized the Patriarch. He said that publicly, at a meeting where I was. But when Solzhenitsyn was expelled, the then Metropolitan Seraphim, who was assistant to the Patriarch, put out a statement saying that Solzhenitsyn did not represent the views of the Russian Orthodox Church. It was quite a critical letter that was published in the Times against Solzhenitsyn. Metropolitan Antony wrote another letter to the Times, saying publicly, “I, as a hierarch of the Moscow Patriarchate, dissociate myself entirely from the remarks that have been published under the name of Metropolitan Seraphim.” I think he phrased it like that because he doubted whether Metropolitan Seraphim had really said this. He thought the letter had probably just been dictated to him. But he publicly dissociated himself and said, “We honor Solzhenitsyn as a true son of the Orthodox Church.”

So, Metropolitan Antony was independent. But I felt that if I joined the Russian Church I must join the Zarubezhnaya Tserkov, and many people discouraged me from that.

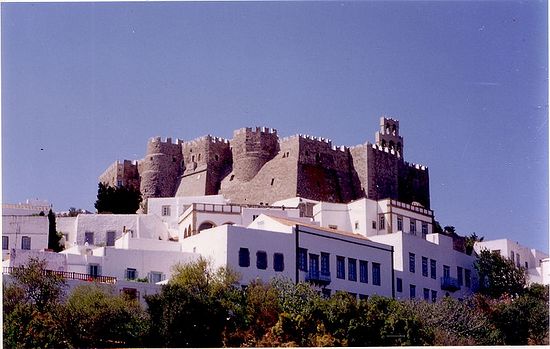

But for your [monastic] vows you went to St. John the Theologian Monastery on Patmos.

Yes, that’s right. Just to recall the sequence of events: In 1958 I became Orthodox in the Greek cathedral. Bishop James, the assistant bishop received me. He then told me to go for confession to Fr. George Sheremetev. So it was at his own suggestion, with his blessing, that I chose Fr. George as my spiritual father. At that time there were normal relations of concelebration and Communion between the Zarubezhnaya Tserkov and the Ecumenical Patriarchate. It was only at a later date — I think around 1970 — that relations became quite difficult.

So, I continued belonging to the Greek Archdiocese, but with Fr. George as my spiritual father. I tended to go, on the whole, to Russian churches. But Fr. George did not object to my going to the Russian parish in Oxford that was under the Moscow Patriarchate. He did not take an extreme view here. He said, “The Moscow Patriarchate is an Orthodox Church. They have true priests and true sacraments. We do not doubt that. But in a free country we must be free.” That was his position. He didn’t mind if I went to the church here.

Then in 1963 I went to the monastery of Vladyka Vitaly in Montreal and spent six months there. I returned in 1964 to England. There was a new Archbishop of Thyateira, the Greek Archdiocese: Athenagoras (not to be confused with Patriarch Athenagoras). I had met him earlier, when I was in Princeton in 1960. He offered me the opportunity to come and work for him as his English secretary, and he said he wished to ordain me as deacon. It was then, after I had visited Vitaly, that Fr. George, as my spiritual father said: “I do not bless you to be ordained priest in the Russian Church in Exile.” He said, “Our clergy are becoming very narrow.” He wasn’t very explicit about this, but I think he foresaw the attitude that would be taken by Metropolitan Philaret when he was head of the Exile Сhurch, when he (more or less) condemned the Ecumenical Patriarchate as having fallen away from the Orthodox Faith. He didn’t say that absolutely explicitly, but I think Fr. George was aware of the attitude by some people at that date in the Exile Church who were inclined to say, “We are the only true Orthodox Church (with, perhaps the Old Calendarists in Greece).” Fr. George was not, I think, of that outlook. I think he foresaw that this was a growing attitude in the Church in Exile, and he said to me, “You will find that too narrow.”

I first came across this attitude when I was in Jordanville as a layman in 1960. I went to stay there with a letter from Mother Elizabeth, and I was made very welcome. But then Fr. Constantine (Zaitsev) discovered that I belonged to the Greek Church, and he was not very pleased about that. He said to me, “Yes, we are in communion with the Ecumenical Patriarchate, but this will not last very much longer.” That was the first time that I had come across this attitude in the Russian Church Abroad. I went to him for confession, he gave me absolution and blessed me to receive Communion. But he said, “It will be better if you only go to Communion in Russian churches,” meaning those of the Zarubezhnaya Tserkov. That was what I did at that time. Fr. George Sheremetev never adopted that attitude.

When I told Fr. George Grabbe, the future Archbishop Gregory, that I had been told that I should not go to Communion in Greek churches if I received Communion in the Russian Church Abroad, he was very indignant. He said, “Who told you that?!” I didn’t mention Fr. Constantine’s name because I didn’t want to make trouble. I just said, “Oh, well — I heard this.” At that time Fr. George Grabbe was very definite: “We are in Communion with the other Orthodox Churches, except for the Moscow Patriarchate, and except for difficulties in Jerusalem.” Because, I think, the Patriarch of Jerusalem in the 1950?s said that clergy of the Church Abroad could not celebrate in the Holy Sepulchre. Jerusalem changed in attitude later. But at that time he was most emphatic that we are in communion, that we have brotherly relations — particularly, he said, in the Patriarchate of Alexandria out priests in North Africa have very close contacts with the Greek clergy. For example, they arranged their holidays so that when the Greek priest goes on holiday the Russian priest looks after the people, and when the Russian priest goes on holiday his people are looked after by the Greek priest.

Well, of course, Fr. George Grabbe changed later and adopted very much the strict view, under the influence, I fear, of Fr. Panteleimon of the Monastery of the Holy Transfiguration in Boston. That’s all sort of background to my time.

When I was ordained priest by the Greeks in 1966, for several years I served regularly in the Russian convent in London with Mother Elizabeth. Fr. George Sheremetev was the chaplain to the convent. His health was bad. He had trouble with his heart, and he was always worried that he might have a heart attack during the Liturgy. So he asked me to come and help with feasts like Christmas (on the old calendar) when I was free and didn’t have duties in Oxford. That continued until 1970.

One day, when I had gone up to celebrate a weekday Liturgy at the convent, Fr. Panteleimon of Boston happened to be there. He clearly — this was 1970 — was not at all pleased to discover that I celebrated the Litrugy at the convent. He made that clear to me. I said to him, “Alright. You are here. I didn’t know you were coming. You celebrate the Liturgy tomorrow for the sisters.” He said, “No, you celebrate. Because you have come especially. They have invited you.” And he came to the service. He didn’t have Communion, but he stayed. But at the end he said, “This is only permitted by extreme economy, and it will not last much longer.

A few weeks later, Mother Elizabeth received a letter from Metropolitan Philaret saying, “It will be best if you do not invite Fr. Kallistos too often to celebrate in the convent.” He did not actually say that she should never invite me, that I should not be allowed to celebrate there. But Mother Elizabeth said (and I said too) that it was clear that he did not want me to celebrate in the convent. Therefore it was better that I should cease doing so. That was in 1970. I no longer went to serve in the convent.

In 1971 Fr. George Sheremetev died, but he was not directly involved in this question of whether I was to serve in the convent or not.

Vladyka, in this same year a decision was made at the council in Montreal about the reception into Russian Church Abroad by baptism only. I wonder if your book on Eustratios Argenti played any role, because Fr. George Grabbe was very impressed by that book, I understand.

That is interesting. He never himself told me that he was impressed by that book. I suspect that the book might have influenced the course of events, because I did give in that book a very clear account of the controversy at Constantinople in 1755, and also I gave a full summary of the arguments of Eustratios Argenti, who was the theologian who chiefly supported the practice of rebaptism. So, yes, I think that this may have played a part in their decision. I never heard any explicit confirmation of that. But Fr. George Grabbe undoubtedly knew that book. I almost certainly sent him a copy when it was published. That would have provided an argument in support of the very strict position of rebaptism. And I pointed out how figures like St. Nicodemus of the Holy Mountain in the eighteenth century, the editor of the Philokalia, in his book on the canons, defends the practice of rebaptizing converts. He says, “In the past converts have been accepted by chrismation from the Roman Catholic Church. This has been done by economy. But now the time for economy has past and we should apply strictness — akrivia.” This was his argument, an argument that some canonists, like John Erickson of St. Vladimir’s, do not accept. They say this is a misinterpretation of economy. But certainly the arguments on all of this were set out in my book on Eustratios Argenti. It’s interesting: that book has just been reprinted. So it’s evident that there’s a continuing interest in it. There are some people, certainly, in the Church of Greece, and particularly on the Holy Mountain, who take the view that converts should be received by baptism, who follow the position of strictness.

Vladyka, has your treatment of this issue changed with time? If you were now to write a preface to this book, what would you say?

In my original book, I did not myself clearly adopt the opinion that converts should be baptized. I myself had been received by chrismation as, of course at that time, in the 1950?s, was the practice in the Russian Church Abroad. After all, the Grand Duchess Elizabeth, St. Elizabeth the New Martyr was received by chrismation, and the Empress Alexandra equally. So I did not myself come out in a definite way defending the position of Argenti. But I put all his arguments, and I didn’t say that the arguments were untruthful and unconvincing. I emphasized the point that Orthodox Church practice has varied. The Russians in the early seventeenth century baptized Roman Catholics. In the council of Moscow in 1766-67 they ceased to do this because of pressure from the Greeks who were present, who said that they must be received by Chrismation. Then, when the Russians followed this practice the Greeks themselves changed to baptizing Roman Catholics in 1755. So I emphasized that, in fact, in the history of the Orthodox Church, both practices have existed. I did not say that only one is acceptable, but I did state the arguments of Argenti quite emphatically.

Perhaps I should mention how I came to write this book on Argenti. This was in 1959. I was approached by a Greek layman in London, Philip Argenti, a descendent of Eustratios, who had written a whole series of historical works on the island of Chios. He was quite important as a scholar. He wanted a book to be written about his ancestor, but because he was not a theologian, he did not feel that he could write such a book himself. It was he who invited me to write this book. He even paid me a small sum for doing this, and he gave me materials relating to his ancestor. I don’t think I could have written the book without his help. I acknowledged this. So, in fact, it was not so much my own initiative as his invitation that led me to write this book, hence my involvement and interest in all of this.

If I was writing a new introduction, I think I would say that there are difficulties about the view taken by St. Nicodemus that you have the two ways: economy and strictness. I would mention the views of Orthodox canonists who say that this is a misunderstanding of economy, and you cannot use economy this way. I would say that the discrepancy between the different Orthodox practices is not so easy to resolve as I thought then, taking the view of Nicodemus. So I would be more guarded, but I would still leave unchanged my exposition of the controversy which, to the best of my knowledge, has not been superseded. New facts have not come to light which would contradict the account that I have given.

On this topic of oikonomia, what would be your take on the notion that empty forms of the properly performed baptism are filled with grace at the moment of reception in any mode of the reception? So if you are receiving a priest through repentance, the Church is able to grant through this act whatever is needed for his ministry, without recognizing his baptism. That’s another interpretation of sacramental oikonomia.

Yes, I am aware indeed of this particular explanation. I am not very content with this. I feel that oikonomia can be used to permit a departure from the strict rules of the Church, but it cannot be used to make something exist which did not previously exist.

Now a typical example that I would give of a justified use of oikonomia which is not controversial, is that the canons say that a deacon should not be ordained under the age of twenty-five, or a priest under the age of thirty. In practice, in all Orthodox Churches people are ordained earlier than these dates. That, I think, does not raise any controversial issue. It is a relaxation of the rules. But to say that a person who has been unbaptized, who has received an external ceremony of baptism, but has not been baptized, that somehow his baptism could be made to exist by economy through the use of chrismation — that I find quite difficult. I don’t think economy can be used to justify creating something that did not previously exist. I would probably write this in my introduction.

Could we return now to your time with Vladyka Vitaly in Canada?

Vladyka Vitaly wrote to me in the early ’60?s, initially simply saying that he had heard about me and was praying for me. It was a very friendly letter. He had heard about me from a fellow student whom I had gotten to know while I was at Princeton in 1959-60, who was Russian, who came from Canada, who knew Vladyka Vitaly and had told Vitaly about me. Then Vitaly wrote another letter inviting me to come to Montreal and to help him with English Orthodox work.

When I actually went to Montreal he received me very coldly. I realize in restrospect, though he never said this, that he was not pleased with my book “The Orthodox Church,” my first book, a Penguin book. He considered it to be far too liberal. I infer this from things that I heard, but he never said that to me explicitly. But I realized when I came to Montreal that he was not pleased with me. After I’d been there for about six months. He said, “This is not the place for you.” He also said, “You have no proper vocation to the monastic life.” He was quite definite and outspoken. I’m sure that he spoke with sincerity and not out of malice. I respect him. Naturally, I found his words difficult.

When I was living in his monastery, sometimes he used me to help in the printing room. He had another monastic house outside in the country, where they did farm work, but I never went there. I was only in Montreal. But most of the time he said to me — he knew I had to finish my doctoral thesis at the University of Oxford — and he said to me, “Alright, you concentrate on that and you may write and study.” He did not employ me very much to do work in the monastic house. I think he saw my visit, from the start, as only temporary.

But you yourself were not that sure. You were thinking about staying.

Yes, I was thinking about staying, initially. When he finally said, “You cannot stay,” I actually felt a certain sense of relief. But until then I had been willing to stay and struggle. But I suddenly felt that he was right. That is why I don’t bear him ill will for what he decided. I think he considered that I was, by his standards, far too liberal in my approach to Orthodoxy.

He also mentioned to someone else, not to me, that he thought I was a spy. Mother Elizabeth in London heard about that. She spoke to me with great contempt of that opinion. She said, ironically, “Typical D.P. outlook!” After all, he was not a displaced person, but he could have been regarded as such. I knew from what others told me later that she had difficulties with him when he was priest in London, or rather when he was bishop in South America, and he wanted her nuns to go out and help him, and she said no. He was apparently very annoyed about that and wrote her a very fierce letter. But Archbishop John (Maximovich), St. John, told her “Don’t reply to that letter.” (That was a background, there, that had nothing to do with me.)

But when I came back from my time with Vitaly, Fr. George said, “I knew you wouldn’t stay.” He told me how he had found Vitaly very hard-lined when he was parish priest in London.

They were probably together in northern Germany.

Ah, perhaps they were. I don’t know. That’s possible, yes. I think the real reason was not that he seriously thought I was spy (perhaps there were moments when he did), but he just felt I did not fit, and probably he considered I was too independent. When I published such a book he realized that here was somebody who had already studied widely and had made a certain reputation. He wanted somebody who would be more maleable, that he could shape according to his own wishes. I saw in his monastery that the monks were very devoted to him. Well, one was not so close. But certainly the future Bishop Paul was very devoted to him. The others, too, I think, did respect him deeply. Probably he felt I would be too independent, and he was probably right.

Vladyka, you mentioned The Orthodox Church, which is very unique. There are many other attempts to write such an exposition, but I don’t think there are any other books that can compare with the success of yours. There are a number of editions. I remember that one them had something on the back about the author saying that, at the moment, he resides in Montreal.

Yes. It may have even said that I am a member of the Russian Church Outside Russia. That’s true.

It was probably the second one, not the one that Vladyka Vitaly saw.

Yes, it was published in ’63, the year I went there. The first edition was in 1963. I made minor revisions to various editions, to bring it up to date, but I did not do a major rewriting until 1993. Then I rewrote about one third of the book, particularly those parts relating to the Orthodox Church under communism. With the fall of communism, naturally the Church situation had changed radically within Eastern Europe and Russia and therefore it needed to be a great deal altered.

I think that the first edition of 1963 was written a good deal under the influence of the Russian Church Abroad, and that I certainly was quite critical there of the Moscow Patriarchate. Initially, for example, Bishop Antony (Bloom) would not allow my book to be sold in his bookstore. I felt in 1993 that some of the things I had said there were too harsh, and I did modify them. I continued, however, to keep the parts of that book where I expounded the point of view of the Russian Church Abroad. I felt when I wrote it in 1963 that all the material available in the English milieu was favorable to the Moscow Patriarchate, and particularly the material that was used by the Anglicans. That was partly why I wanted to express the other point of view as to why the great majority of Russians in the emigration did not choose to belong to the Moscow Patriarchate.

I found it necessary also to mention that there was a Catacomb Church in Russia. Of course, material put out by the Russian Church Abroad did mention these things, but it, on the whole, did not circulate at all widely. So I felt that it was only right to state the other point of view. I was criticized for being, as people saw it, too favorable to the Church Abroad. That was a point taken up by a number of reviewers of the book. I even remember one of the bishops of the Moscow Patriarchate, Archbishop Alexis (van der Mensbrugghe), saying to me, “There is not Catacomb Church in Russia!” There was, he said, in the twenties and thirties, but since, he said, the Second World War, “it has not existed.” And he even said, “I am a bishop of the Moscow Patriarchate. I know these things.” Well, we now, of course, have plenty of evidence that there was indeed a catacomb movement. Perhaps we should not say a “Catacomb Church,” because it is not clear that there was a single hierarchical organization. But there wer certainly, even in the forties and fifties, bishops who did not belong to the Moscow Patriarchate. Of course, evidence has come to that. But at that time I was a lone voice. That was not so widely said.

I think they were perturbed in the Moscow Patriarchate that here was a book published by a major non-religious publisher — Penguin’s — whose books get into ordinary bookshops, not just specialized religious bookshops. And this was perhaps the first book to be issued in this way by a major non-religious publisher on the Orthodox Church. I think they were perturbed.

But I was also criticized by Fr. George Grabbe for being too favorable to ecumenism in the final chapter. That may be also why Vladyka Vitaly was not so pleased when he saw this book. I have reason to believe that he had read it actually, or had read the parts that interested him. If anything, in the 1993 revision, I am a little less negative about Christian unity, though I kept the statements in my first edition unchanged — the claim of the Orthodox Church to be the true Church of Christ, and that we do not accept any form of the “branch theory” of the Church.

The Russian Church Abroad identity was always closely connected with Russian nationalism and anti-communism. This helped its self-definition; like it or not – as Fr. Alexander Schmemann said, it definitely has style. But now that communism has ceased to exist, what identity is there for it to recover?

What I have always admired in the Russian Church Abroad is its faithfulness to the liturgical and ascetic spiritual traditions of Russian Orthodoxy in particular and Orthodoxy in general. I was always impressed by their faithful performance of the church services and their re-printing of the liturgical books, at a time when they were very difficult to obtain. I helped priests of the Moscow Patriarchate, who were afraid to write directly to Jordanville, to take church books back into Russia. I asked one priest if he would have any trouble with the customs, taking books which included prayers for those suffering under atheist oppression, but he said no, as the Soviet customs officials could not read Slavonic.

I also admired the faithful presentation of liturgical piety at a time when other Orthodox, like the Greeks in America, were making changes in the services. I had not visited Russia at that time though of course there too the services were properly performed.

The Church Abroad also upheld the spirituality, for example, of the tradition of the Philokalia, Saints Theophan the Recluse and Ignaty (Brianchaninov).

Now there is a restoration of communion between the Church Abroad and the Moscow Patriarchate. I am very pleased about this and also that the Russian Church Abroad retains its own identity. Of course it would have been difficult for the Moscow Patriarchate to condemn Metropolitan Sergius (Stragorodsky) and deny their own identity, but they have canonised the New Martyrs of Russia who are now venerated by the whole Russian Church.

Since the restoration of communion there has been much more openness by the Church Abroad towards Russia and to Orthodoxy in general. Yet they have continued to be faithful to their liturgical and ascetic traditions to an extent which is not found in the same way among other Orthodox. This emphasis is very much needed today.