When a faith is highly traditional—so traditional that her Tradition is seen as nothing less than the presence of God living and breathing in the life of the Church—it is sure to clash with the sensibilities of a modern, critical, and pluralistic culture such as our own.

One of the many sources of friction between the Orthodox Church and contemporary culture is in the exercise of authority.

As Lockean, democratic, social-contract theories, with an emphasis on individual rights, have come to dominate the way we instinctively think about morality and social life over the past few centuries, Christian moral and metaphysical foundations have eroded. This largely accounts for our extreme distrust of authority in every form. We don’t want kings or emperors, we want democracies; we don’t want bishops rightly dividing the word of truth and accountable to the Church and Tradition, we want our singular conscience and the Bible; we don’t want stable social institutions, we want revolutionaries, iconoclasts, and ‘progress.’ This modern sickness runs deep.

One of the primary spiritual manifestations of this illness can be seen in our disposition toward the sacraments of the Church. In particular, holy orders, confession, the Eucharist, and the relationship between them.

For many who come in contact with the Orthodox Church in our modern age, one of the more jarring aspects is a zealous guarding of the chalice by her bishops and presbyters. If someone is not a baptized Orthodox Christian in good standing, having recently confessed, they are turned away from the communion chalice—though practically this entails refraining from approaching in the first place. For contemporary American Christians, this practice appears to be a grievous sin and a manifestation of hubris on the part of the Orthodox Church. But the criterion of truth and love is not based upon the cultural sensibilities of modern America, but rather Christ and his Church.

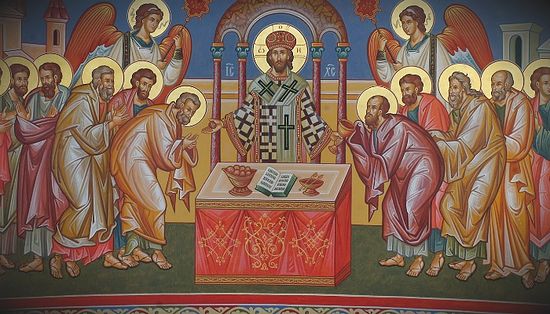

From the very beginning, the Eucharist was known to be Christ’s true Body and Blood (John 6:47-58; Matt. 26:26-28), which was a tangible expression of—and participation in—the unity of the Church (1 Cor. 10:16-21). The Eucharist was also believed to be dangerous—both spiritually and physically—for those not rightly discerning this truth, or being otherwise unprepared to receive (1 Cor. 11:23-30).

Given this reality, it is not surprising that St. Justin Martyr writes (second century):

And this food is called among us the Eucharist, of

which no one is allowed to partake but the man who

believes that the things which we teach are true, and who

has been washed with the washing that is for the remission

of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as

Christ has enjoined. For not as common bread and common

drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus

Christ our Savior, having been made flesh by the Word of

God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so

likewise have we been taught that the food which is

blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our

blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the

flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.

—First Apology 66

And St. Ambrose of Milan (fourth century):

He gave [the Eucharist] to the Apostles to distribute to a believing people, and today He gives it to us, for He, as a priest, daily consecrates it with His own words. Therefore, this bread has become the food of the saints. —On the Patriarchs 9, 38

Also, St. John Chrysostom (fourth century):

As it is not to be imagined that the fornicator and the blasphemer can partake of the sacred Table, so it is impossible that he who has an enemy, and bears malice, can enjoy Holy Communion . . . I forewarn, and testify, and proclaim this with a voice that all may hear! ‘Let no one who has an enemy draw near the sacred Table, or receive the Lord’s Body! Let no one who draws near have an enemy! Do you have an enemy? Do not approach! Do you wish to draw near? Be reconciled, and then draw near, and only then touch the Holy Gifts!’ —Homily 20

Of course, Chrysostom is speaking of fornicators and blasphemers who have not yet repented and been reconciled to the Church. It wasn’t up to the individual to demand that the sacred Body and Blood were due to him, rather it was (and is) the responsibility of the priest to guard the sacred mysteries of Christ on behalf of the entire Church.

This wasn’t solely because participation in the Eucharist is a visible declaration of the unity of—and true participation in —Christ and his Body (making it an impossibility for those outside His Body to be ‘in communion’), but also out of love for both the non-Orthodox and the unprepared. For such, partaking of the Eucharist would be ”eating and drinking damnation” (1 Cor. 11:29), and so the ministers of the sacraments blithely distributing it to any who ask for it would be both irresponsible and unloving.

This was the consistent belief and practice of all Christianity up to, and even including, the Reformers. Article XXIV of the Lutheran Augsburg Confession states that “Chrysostom reports how the priest stood every day, inviting some to Communion and forbidding others to approach,” as a justification of the continued practice of ‘closed communion.’ This remained the norm in Protestant denominations until the last century.

As Christ delivered himself up to death for the Church (Eph. 5:25); brought salvation to the world through the Holy Spirit in the Church which is His body (1 Cor. 12:27); delivered to her the power and duty to baptize (Matt. 28:19-20); the power and duty to both remit and retain sins (the latter being especially difficult for modern people to accept; John 20:23); and the power to bind and loose things in heaven by way of earthly ministers (Matt. 18:18)—it is clear that the Church is the guardian of the sacred and dread mysteries of Jesus Christ. This fact is borne out in the writings of the fathers, with nary a word to the contrary among the orthodox.

On the subject of heretics and their lack of fear, Tertullian writes:

But where God is, there exists “the fear of God,

which is the beginning of wisdom.” Where the fear of

God is, there is seriousness, an honorable and yet

thoughtful diligence, as well as an anxious carefulness

and a well-considered admission to the sacred ministry and

a safely-guarded communion, and promotion after good

service, and a scrupulous submission to authority, and a

devout attendance, and a modest gait, and a united church,

and God in all things.

—The Prescription Against Heretics 43 (emphasis

added)

With an appropriate fear of God, and an understanding of his holiness (the priest begins distribution of the Gifts in the Divine Liturgy while telling communicants “with fear of God, faith, and love draw near”), the duty of those bishops in apostolic succession (along with their presbyters) to guard our sacred communion seems obvious.

As the late-first century document the Didache or Teaching of the Twelve Apostles, says:

Let no one eat or drink from your Eucharist except those who are baptized in the Lord’s Name; for concerning this also the Lord hath said: ‘Give not that which is holy to the dogs.’

This reality can raise questions concerning those who are baptized in non-Orthodox traditions, branching off into questions of ecclesiology that can’t be fully addressed here (you can browse other articles on ecclesiology here). At the end of the day, the Orthodox Church maintains that there are no sacraments outside of the Church, and so the first step towards receiving holy communion is being baptized into the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic Church.

Christ desires all to draw near and receive of His holy and life-creating mysteries. But let us not be deceived by an erroneous, yet popular, belief in the sovereignty of the individual. Grace is freely-given, not demanded and seized.

May we all strive for Christ and his Church with a fear of God, in repentance and humility. May we all receive of the saving, transfiguring Grace of the Holy Trinity that flows from a properly guarded chalice.