SOURCE: Juicy Ecumenism

By Brian Miller

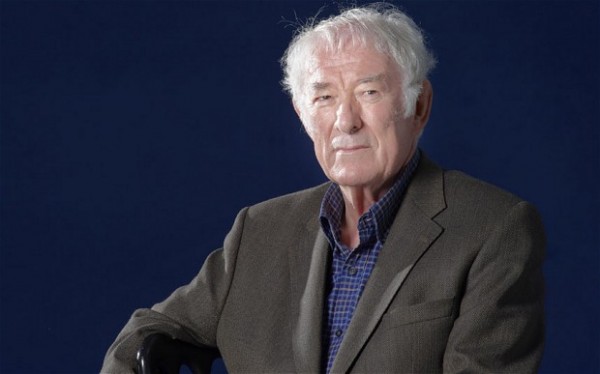

Photo: The Telegraph

Photo: The Telegraph

“O flower of warriors, beware of that trap.

Choose, dear Beowulf, the better part,

eternal rewards. Do not give way to pride.

For a brief while your strength is in bloom

but it fades quickly; and soon there will follow

illness or the sword to lay you low,

or a sudden fire or surge of water

or jabbing blade or javelin from the air

or repellant age. Your piercing eye

will dim and darken; and death will arrive,

dear warrior, to sweep you away.”

When I learned that the Irish poet Seamus Heaney had passed away I made a long overdue trip to the local bookstore to purchase a copy of his Beowulf translation. I had little knowledge of the man or his works, and, I’m ashamed to say, had spent twenty-two years on this earth without reading the ancient English work. I am now profoundly grateful to have been introduced to both.

Heaney was born in 1939 and became one of the 20th century’s most important poets. A Catholic who was raised in staunchly Protestant Northern Ireland, he was also a deeply religious man.

Since the trip to the bookstore, I have only had time to become faintly acquainted with his actual works, but I have managed to read his translation of Beowulf through twice. In creating this new translation, Heaney is said to have made Beowulf relevant for the next age. If that were his only life accomplishment we would still owe him an enormous debt of gratitude.

Beowulf is a character caught in a pivotal moment in history. He arrives on the scene not long after the introduction of Christianity to the people of the North. The influences of the old Paganism, one we know comparatively little about, is still found throughout the work. Indeed, all the references to the Christian Bible are from the Old Testament. In a lecture, Heaney said this is because “The poet is more in sympathy with the tragic, waiting, unredeemed phase of things than with any transcendental promise.”

Heaney further explained that the introduction of Christianity caused the author to be “displaced from his imaginative at-homeness in the world of his poem – a pagan Germanic society governed by heroic code of honour, one where the attainment of a name for warrior-prowess among the living overwhelms any concern about the soul’s destiny in the afterlife.” Beowulf, therefore, represents that crucial step from paganism to Christianity.

Many critics through the years have viewed the poem as being of interest only for its historical uniqueness, but dismissing it as not having any literary significance in its own right. Its ancient and simple hero who follows a strict code of honor brings the modern mind to conclude that it must have been the work of a simple and unimaginative mind who simply recorded stories from the pagan and distant past. “A half baked native epic,” as one critic described it. Heaney, however, disagreed, and saw Beowulf as a work of art in its own right.

In support of this conclusion, he relied on the work of J.R.R. Tolkien. Tolkien argued there might be something wrong with our “modern judgment” if we cannot see that the work is certainly more than just a folk tale. Tolkien reasoned that “the high tone, the sense of dignity, alone is evidence in Beowulf of the presence of a mind lofty and thoughtful. It is, one would have said, improbable that such a man would write more than three thousand lines on matter that is not worth serious attention.”

Tolkien continues that “Beowulf is not, then, the hero of a heroic lay, precisiely. He has no enmeshed loyalties, nor hapless love. He is a man, and that for him and many is sufficient tragedy…The poet looks back into the past, surveying the history of kings and warriors in the old traditions, he sees that all glory, ends in night… The author of Beowulf showed forth the permanent value of that pietas which treasures the memory of man’s struggles in the dark past, man fallen and not yet saved, disgraced but not dethroned.”

Beowulf is a great poem, and like the Aeneid or the Iliad is something to be read and pondered over. The most immediate thought that came to my mind, however, is that Beowulf represents the end of paganism. Conservative Christians are often found lamenting that the world is returning to paganism. I’ve often felt there is something off about this prescription. Whatever the modern world is suffering from is not caused by reading too much Cicero or having heroes like Pious Aeneas.

C.S. Lewis believed something similar and expressed his thoughts in the short poem Cliché Came Out of Its Cage. “You said ‘The world is going back to Paganism’. – Oh bright Vision!” Lewis exclaims. He then describes the pagan world of sacrifice made of young men standing in silent respect before their elders, of reverence for the age being as seasonable as rain, and of men dying in defense of their city. He further praises the Northern Pagans, from which Beowulf sprang, who believed the world would end in anarchy, but that the righteous would be found worthy to stand with the gods at the final defeat. He described women who walked back into burning buildings to die with the men of the city, and obedient daughters who were guided by their venerable mothers. Lewis closes by asking, “Are these the Pagans you spoke of?” and then sharply commands to “Know your betters and crouch.”

G.K. Chesterton, who no doubt influenced Lewis on the topic, put it much more succinctly by saying:

“I am very glad that our fashionable fiction seems to be full of a return to paganism, for it may possibly be the first step of a return to Christianity. Neo-pagans have sometimes forgotten, when they set out to do everything the old pagans did, that the final thing the old pagans did was to get christened.”

If the modern world is returning to paganism its end will not, as the leftists believe, be mankind’s return to a state of nature where he peacefully eats acorns with his fellow man. However, neither, as the conservatives believe, will it mean the end of the world. The end of paganism is Beowulf.

As the poet said himself, “The truth is clear: Almighty God rules over mankind and always has.”