Humanism Sets the Stage

The rallying cry of Renaissance Humanism was “the genius of man” and the “extraordinary ability of the human mind” (Gianozzo Manetti, On the Dignity and Excellence of Man, 1452).

The Renaissance served as the emancipation of Western man from the “shackles” of a Papacy indistinguishable from the state in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, paving the way for the centrality and superiority of the individual in all things — whether art, politics, philosophy, or religion. When this cultural shift came in contact with the Christianity of the Latin West, the effects were most palpable, and its end unstoppable. Hus, Wycliffe, and Luther would be but the beginning.

The irony of this elevation of humanity above all things (including God-via-Church, as well as divine-right kings and kingdoms) is that the religion of the Reformation was by-and-large incredibly negative in its human outlook — at least, selectively so. The “genius” of man was counter-balanced by his “total depravity” in the minds of the Calvinists. And yet, somehow, “totally depraved” man had the ability to reasonably determine the parameters of a re-born Christianity — a future that led the Reformers away from both the shadow of the Latin Church-State and the iron fist of the Papacy.

Emerging from this paradox of both man-centeredness and self-deprecation was an increasingly critical outlook, and the advocation of a new kind of textual criticism, where the unbelief of Renaissance Humanism is directed not only towards the Church, but also towards the Sacred Scriptures themselves (e.g. B.B. Warfield, the German Reformed, and Bart Ehrman in the present day). Many of the Reformers were clearly eager to jettison 1,500 years of apostolic tradition — ascribing that kind of tradition to mankind under the yoke of “total depravity,” while their new traditions were somehow free from this bondage and able to rise to the level of man’s “genius.”

But what lies at the heart of both Renaissance Humanism and excessive versions of textual criticism?

Is it faith? Is it a sincere, faithful admiration for both the Scriptures and the teachings of Christ and his apostles?

The Idealization of Nicaea?

In a recent blurb at First Things (titled “Nicea for real”), Peter Leithart reflects on a lecture by Thomas Buchan on the “idealization” of the first Council of Nicaea (AD 325, aka the First Ecumenical Council):

Thomas Buchan gave a superb response paper at the Ancient Evangelical Future Conference at Trinity School of Ministry. Buchan’s paper was dynamite under every idealization of Nicea and its effect on the church.

The “idealization of Nicea and its effect on the church” would seem to indicate that Leithart does not believe that the Creed of Nicaea (and later of Constantinople in 381) had an impact of any significance on the history and theology of the Church — at least not in the period in which it was composed. However, this comes from the perspective of a theological archaeologist: looking back to certain tidbits of history and piecing together a re-born (“renaissance”) version of history in the present.

Regardless, ever since the fourth century, the Creed has been significantly impactful. Christians east and west today continually recite it as part of their communal, liturgical worship, as well as in private devotion. That it took a while to “catch on” in the tumultuous days of the fourth and fifth centuries does not indicate that our understanding of its impact today is somehow “idealized” or even mythical. The resulting, incarnate Body of Christ today — that is, the actual, apostolic Church that lives and breathes by the Spirit of God — exists largely because of the Creed; because of the men who fought, were tortured, and died for it.

It is bad form to downplay its importance, simply because the earliest centuries of the Church were riddled with controversy — something no Catholic Christian would deny, as this is part of the life of the Church (1 Cor. 11:19) and not a sign of any defect or essential disunity in her. While the latter might support Leithart’s de-incarnational ecclesiology and archeological historiography, the Scriptures will have no part of it.

Just Another Creed?

He continues:

For starters, he pointed out that the Nicene Creed was not the only creed in circulation. There were many pre-Nicene baptismal creeds, and the effect of Nicea was not to eliminate but to regulate these. The Nicene Creed, further, was not originally intended as a confession for the whole people – not a liturgical creed – but instead a creed for bishops. It was first used as a liturgical creed by the Miaphysites as a protest against Chalcedon; pro-Chalcedon churches began using the creed liturgically as a reaction to the Miaphysite use. It wasn’t until near the end of the sixth century that the Nicene Creed was used liturgically in the West, first in Spain.

It is certainly the case — especially in the West — that other creeds, such as the so-called Apostles’ Creed (cf. Antipope Hippolytus, Apostolic Tradition) were in use alongside that of Nicaea. This does not, however, undermine the importance of Nicaea for the Church as a whole. Nicaea was likely of eastern (perhaps Antiochene) origin (cf. Cyril of Jerusalem, Catechetical Lectures), as was most influential theology at this point in history.

The creed was certainly composed initially for the sake of bishops, as it was primarily bishops who were involved in such synods to begin with. The importance of the Creed was in unifying the bishops of the various local churches, so that their own personal rule of belief was also in line with their rule of prayer. As successors to the apostles, the bishops must necessarily have been in agreement on such key issues. Yes, this took a while to sort out, but everything of great importance in the Church always does. These things don’t happen overnight, and the same was the case with the Scriptures.

While the adoption of the Creed may have perhaps taken longer in the West (being largely overrun by both Arians and barbarians), it was never so disputed in the East — that is, in the true heart of the Empire after Ss. Constantine and Theodosius the Great. The slow adoption of Nicaea in the West has more to do with cultural and political hindrances in the West than it does with any hesitancy of the Church to maintain orthodoxy as the unified, theanthropic Body of Christ.

The Perceived Disunity of the Church

Leithart further notes:

Buchan added that, contrary to popular accounts, the term homoousios didn’t immediately win the field, even among pro-Nicene theologians.

In fact, virtually no one particularly liked the term homoousios. During the 330s and 40s, Athanasius devoted his energy to exegetical refutations of the Arians, and rarely used homoousios. It comes to the fore in Athanasius’ work only in the 350s, against the virulent neo-Arianism of Asterius.

This seems to be a favorite angle among non-incarnational, “archaeologist”-style Church historians today — but what are the assumptions?

That the early Church was in complete disarray? That the Church has — even in the “golden ages” of Nicaea — never truly been united? And that, therefore, it would be silly for us to assume that there should be one, embodied, true Church of Christ today?

In any case, “homoousios” did win the day, and it is still a part of the living tradition of the Church. All debating aside, this sort of rhetoric is seemingly only intended to do one thing: to undermine the idea of a unified Church (from the perspective of those who are rejecting it). Once again, it must be stated that very few Orthodox Christians are ignorant of the controversies of the early days of the Church. In fact, many of these controversies are regularly mentioned in both our hymnography and hagiography.

Perhaps a classic analogy would be best served here:

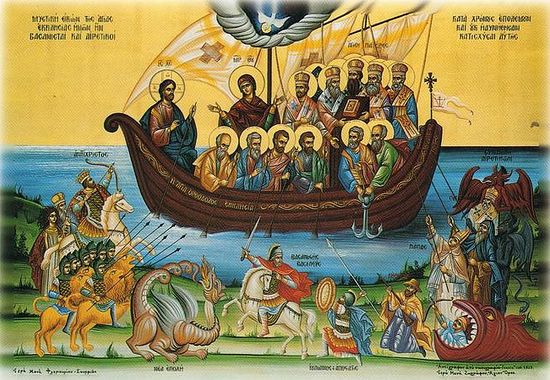

The Church is a seafaring vessel, churning through the tumultuous waters of this life. Many times, the Church must wade through dangerous seas, filled with depth charges, icebergs, and every sort of obstacle that the imaginations of Renaissance men and the cunning of the evil one can devise. And yet, despite these continuous assaults, the ship sails ahead, eventually leaving the controversies in her wake.

Controversy — such as that around the use of the term “homoousios” in the Creed — is not a sign of the disunity of the Church, but rather endures as a testimony to her theanthropic steadfastness and resolve; as a testimony to her being the very Body of Christ (1 Cor. 12:27, etc.), the πλερομα of God (Eph. 1:22-23), and the pillar and ground of the truth (1 Tim. 3:15).

A House (Wrongly) Divided

Finally, Leithart writes:

Buchan ended his excellent presentation with a discussion of the relation of creed and Scripture in the early church. For Augustine, he said, the rule of faith is an aid to novices who haven’t been able to master the whole of Scripture; but he didn’t want readers to stay novices. Creeds were boundaries and guardrails, serving Scripture rather than being served by it. In contrast to some contemporary defenses of the rule of faith, the fathers didn’t think of it as a solution to the complexity and difficulty of the Bible. (I wonder if current uses of the rule of faith still assume the conclusions of critical scholarship concerning the diversity of the Bible.) For the fathers, the creed was not a tool for taming Scripture. The fathers assumed the unity of Scripture, and found that unity confirmed as they read. Recognition of the unity of Scripture made the creed possible; the creed did not impose a unity on a fractured Bible.

In this final paragraph, the real inconsistency of a “critical” approach to both the Church and her history is made manifest.

While the critical, unbelieving eye will continually gaze upon both apostolic tradition and the creeds and councils of our Church, it is never given to shift in focus towards the Bible — despite the fact that the Church, holy tradition, and the Scriptures themselves are all debtors to the same, life-giving person: the Holy Spirit. This is, after all, the very promise of Christ himself in the Scriptures (e.g. John 14:16,26; 15:26; 16:7; Acts 1:4; Rom. 8:26; 1 John 2:27, etc.). Yet, such a belief is completely ignored by those who pledge loyalty to the Bible.

Leithart also glosses over the reality that the idea of “a Bible” is completely anachronistic in the Nicaean era — it was not until around the early-fifth century in the West (at least for the See of Old Rome, per Pope Damasus I) that a canon of the Scriptures was tentatively settled upon for liturgical use. This canon was also different from that of Leithart and other Protestants, driving the anachronism further home, not to mention the widespread illiteracy of laity, the lack of access to personal texts for any but the extremely wealthy, and so on. The place of the Scriptures was the chanted liturgy of the Church, not the common bookshelves of her supposed critics. 1,000-plus years before Gutenberg, there were not an abundance of Bible-thumpers looking to the Creed of Nicaea with scorn.

Further, Leithart touches upon the patristic idea that the Scriptures are for the mature, as expressed by Augustine, for example (cf. the apostle Paul in 1 Cor. 3:2; Heb. 5:12-14). But, using his own words, who among us have been able to “master” the Scriptures, rendering confessions such as the Nicene Creed obsolete? The study of Scripture is not an extension of the “genius” of man, as the Humanists might assert, but is instead related to one’s acquisition or experience of the Holy Spirit (theosis). This only makes sense, as the Scriptures themselves are inspired by the Spirit. By implying that the Scriptures (much like with the Church) are capable of being “mastered” (whether understood or undermined) by mere mortals, Leithart is beginning to let a little bit of his forefathers’ Humanism shine through.

Scripture in Tradition

In truth, it seems that the confusion here is partly rooted in the nature of the Scriptures themselves.

From an Orthodox viewpoint, the Scriptures are part of Holy Tradition — that is, they are part of the tradition of the Holy Spirit, which gives both life and breath to the very being of the Church. Pitting the Creed against the Scriptures (or vice versa) is an approach that is foreign to both the early Church Fathers and to the Fathers of the same Church today. In other words, these are not two different sources of belief that are somehow in competition with one another. This posture of “unbelief” towards the Church (and her Creed), however, underlines the rationale for approaching them as such.

The Creed was not a tool for “taming” the Scriptures, nor were the Scriptures somehow “held over” the sacred traditions of the Church and her Creed. The dichotomy is false, for they are both of the same Spirit. And they both testify of the same God-Man, Jesus Christ: the saving Bridegroom and head of his Body, the Church.

Not only is it historically anachronistic to speak of the “unity of the Scriptures” in an era when there was no unified agreement on what constituted the Scriptures to begin with, but also the resulting division being assumed between the public faith of the Fathers and the words of the Scriptures is completely unrecognizable to the Church — both during the fourth century and today. The sincere faith of our Fathers in this era was that what they were teaching was only what had been taught by the apostles, and this was of course in agreement with the Scriptures, as they came to be gathered together over the centuries.

Concluding Thoughts

To come back to a previous question, then: Of what attitude is both Leithart and Buchan’s approach?

Is it an attitude of faith? An attitude that assumes that the Church is truly built on the foundation of the prophets and apostles, with Christ Jesus as her cornerstone (Eph. 2:20)? That she is truly the fullness of God and the pillar and foundation of the truth?

What we actually find in such an approach to Church history is unbelief. Unbelief not only towards the Church, but also towards the promises of Christ in the Scriptures regarding the Church (Matt. 16:18; 28:20).

When Church history is examined from foundational assumptions such as chaos, disunity, and the “total depravity” of mankind (and therefore a lack of the involvement of God’s Spirit in her life and activity here on earth; a sort of Nestorian or Docetic ecclesiology), the conclusions will always look like those of Leithart and Buchan above — but they are neither historical nor Scriptural ones.