Over the past century, numerous lost scriptures have been discovered, authenticated, translated, debated, celebrated. Many of these documents were as important to shaping early-Christian communities and beliefs as what we have come to call the New Testament; these were not the work of shunned sects or rebel apostles, not alternative histories or doctrines, but part of the vibrant conversations that sparked the rise of Christianity. Yet these scriptures are rarely read in contemporary churches; they are discussed nearly only by scholars or within a context only of gnostic gospels. Why should these books be set aside? Why should they continue to be lost to most of us? And don’t we have a great deal to gain by placing them back into contact with the twenty-seven books of the traditional New Testament—by hearing, finally, the full range of voices that formed the early chorus of Christians?

Obviously, there are a number of assumptions being taken for granted by both the publisher and ANNT editor, Hal Taussig.

For example, did the recently discovered (over the past century or two) “scriptures” contained in this work belong to the same “apostolic age” as the rest of the 27 books of the new testament? The quote above seems to imply that these works were part of the same “conversations” of earliest Christianity, and were not the offspring of “rebel apostles” or doctrines. But is that entirely true? The above quote also suggests that these works have been intentionally “set aside” and “lost to most of us.” This implies that there’s some sort of “cover up” being propagated by the orthodox “mainstream” of Christian thought.

I would contend that what’s missing from these assumptions and implications is a healthy dose of apostolic tradition, combined with an understanding of the Spirit-guided history of both the early and contemporary apostolic Church (which are truly one and the same). Let me give just a few examples of what I mean.

First, one can consider the presuppositions that would inspire this fresh “take” on the new testament “canon” (rule/measure). Ironically enough, Taussig — alongside scholars such as John Dominic Crossan (who authors the Foreword to ANNT) and popular textual critic Bart Ehrman — are all presupposing a broadly “Protestant” view of the scriptures; that is, that the gathered scriptures-as-Bible are to be seen as the sole and final authority for all Christians. For them, the Bible is posited as a “Christian Quran,” and whatever “makes the cut” is alone able to both guide and determine all true dogma, ethics, and piety for Christians.

The Baker Evangelical Dictionary of Biblical Theology states that the Bible (with the Protestant canon) is alone authoritative for Christians because:

- It claims such authority in a variety of ways throughout the various books,

- It has been used by the Church throughout history to settle disputes regarding doctrine, ethics, etc., and,

- The “internal testimony of the Holy Spirit” in individual Christians leads the Christian to recognize it as authoritative and true (as well as the proper canon or collection of books).

Experience, of course, calls into question the last point, as there are innumerable differences regarding both the authority and makeup (canon) of the scriptures among Christians, while the first two can be understood in ways that nullify its overall conclusion(s) regarding “the Bible.” For example, there is no “table of contents” given by any book of scripture, and so any accepted canon must, by definition, be an external authority that ”overrules” the Bible itself. The Bible cannot be the final authority if it must appeal to the Church (or one of Athanasius’ festal letters) for validation. This, of course, presupposes the inspiration of apostolic tradition, with the scriptures as a prime and central aspect of that “conversation.”

By operating according to these Protestant principles, Taussig et al. are suggesting that if we discover any other books that deserve either serious study or devotional reflection on the part of Christians, they must be considered as potential additions to the new testament canon itself. Since the “internal testimony” of the Holy Spirit is an authoritative measuring stick for the very existence and authority of the Bible (according to the broadly Protestant definitions above), any “internal testimony” that leads a group of Christians (in the case of ANNT, they assembled a “council” of various scholars and religious thinkers) to accept a new book (or ten) must, by necessity, be taken into serious consideration. In other words, the end result of these Protestant presuppositions, combined with both a skepticism towards and dissatisfaction of the Biblical canon, is A New New Testament.

Second, this work seems to presuppose that the 27-book new testament generally accepted by all Christians is discriminatory.

Crossan argues in the Foreword that the inclusion of the 2nd-century Acts of Paul and Thekla in ANNT serves as a helpful corrective to the “patriarchal dominance” found in Paul’s epistles to both Titus and Timothy (which he asserts are both apocryphal, and obviously written at least a generation after the apostle’s martyrdom). Of course, any aid given to the cause of women’s roles in the Church by including these Acts is overshadowed by ANNT’s inclusion of The Gospel of Thomas, a 2nd-3rd century Gnostic text that concludes with Jesus telling Peter that women are only capable of being “saved” if they become men first (114:1-3).

Furthermore, Crossan’s assertion is weakened by both apostolic tradition and the witness of the Orthodox Church’s hagiographical tradition (hymnology, devotion, festal celebrations, iconography, etc.). In the case of supposed discrimination or suppression of women, for example, it must be noted that there are a number of women in the Orthodox tradition that are regarded as “equal to the apostles.” Interestingly enough, the martyr Thekla is one such example, as she is commemorated on September 24th each year. The Church has, in fact, preserved stories about her life in both hymnology and readings, which correlates rather closely with the Acts of Paul and Thekla. Rather than going so far as to “canonize” the Actsbecause it contains snippets of truth about a venerable Saint, the Church — guided by the Holy Spirit — has instead received whatever is righteous and true about her life as a venerable part of holy tradition. Because the Church does not view the Bible as the sole or final authority for all matters of faith and life, there is no need to either suppress the truth of Thekla or to elevate her story to the level of scripture. This same apostolic approval of extra-Biblical material can be seen throughout the new testament itself (for example, Jude cites 1 Enoch 1:9 as “prophecy,” while the apostle Paul refers to the location of Paradise in the “third heaven” as found in 2 Enoch, cf. 2 Cor. 12:2-4; 2 Enoch 8-9).

From an Orthodox viewpoint, therefore, the publication of A New New Testament is rather unnecessary. There are many other stories, books, and hymns that find their home in the tradition of our Church, without needing to be added to a revised canon of scripture.

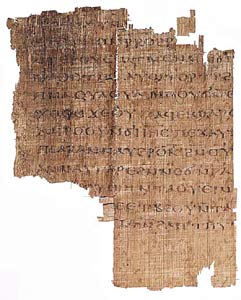

From an historical standpoint, the canon was really almost always a matter of which books were to be read aloud in the liturgy of the catechumens (or, “the liturgy of the word”). Even in the Judean context, the canon was Miqra — “that which is read.” The idea of a single volume bound together as one book or “Bible” is arguably anachronistic, and perhaps most obviously in the way we experience it today (Gütenburg was 14 centuries after the pouring out of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost). By the end of the second century, the four Gospels alone had found their way onto the altars of our churches, but this is a far cry from a Gideon’s Bible in every hotel nightstand.

Beyond this more narrow definition of canon (determining which scriptures are read aloud during the liturgy), the broader canon of the scriptures was debated for centuries among the local churches of the empire, with multiple, different canons finding approval in the sixth Ecumenical Council (near the end of the seventh century). It seems that, for many centuries at least, the determination of a canon of scripture was a mostly local issue, ruled upon by the chief shepherd of each regional church (such as we see with Athanasius’ festal letter in the fourth century). While the canon for both Rome and the East has become far more settled since the counter-reformation (Council of Trent, 17th century) and the various confessions and catechisms of the 17th-19th centuries for the East, there is still a sense of “openness” with regards to its ultimate boundaries.

In the end, I would contend that the only “settled” canon for the Orthodox Church is the collection of daily (and festal) scripture readings throughout the year — or, “that which is read.” The canon of scripture within the tradition of the Orthodox Church is not discriminatory, nor does it suppress the truth of great women-martyrs and Saints such as Thekla; rather, it is largely focused on the encouragement and edification of the faithful, who — for many centuries — were largely illiterate or unable to have scriptural books in their own personal possession. This made the “canon” of “that which is read” to be very important for the first millennium (and more) of the Church. There was no “conspiracy” to hide books from the unlearned, per se, but rather an admirable desire to bring “the best of the best” to the ears of the laity (this also offers a possible explanation for the differences between the Byzantine and “Critical” textforms, I think).

Given this context, then, ANNT can be seen as a project born out of a broadly Protestant framework of presuppositions, combined with a disdain for the traditional collection of books. It isn’t that all of the 10 books included in ANNT are completely useless — as already mentioned, there are parts of Thekla’s story that have been received as tradition by the Church, not to mention the venerable place of the Odes of Solomon (which Crossan wisely notes in the Foreword) – but neither should they be elevated to the level of “scripture,” simply because one might find inerrant truth, apostolic teaching, or any other sort of “internal testimony” of the Holy Spirit within them.

To make such a leap is to concede not only that the Church is without a Spiritual and authoritative tradition, living and breathing among the faithful in Christ, but also that the Bible alone is the final authority for all matters of faith and life. From an Orthodox perspective, such a leap is impossible, in no small part because of our faith in the Church as “the pillar and ground of truth” (1 Tim. 3:15) and “the fullness of him who fills all in all” (Eph. 1:23).

From: On Behalf of All. Used with permission.