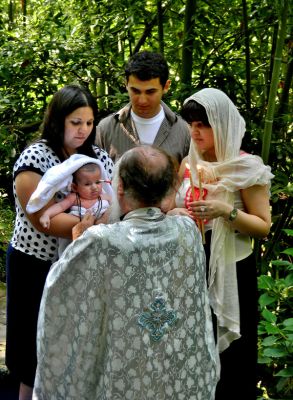

A few months ago I witnessed my first “Churching”—a liturgy said for a new mother when she returns to church, usually 40 days after the birth of her child. Often it is done just before the child’s baptism. The mother waited with her infant daughter at the back door of the church, facing the iconostasis. The priest came and read the Churching prayers and then led them and their friends and family forward to the baptismal font set in front of the royal doors.

Churching follows a long tradition of purification prayers for new mothers used in both the Christian East and West, but they have fallen out of use in some places because people are ambivalent about what these prayers mean, particularly references to the woman’s uncleanness and sin. Some Orthodox priests use the prayers, others avoid them or use them only at the mother’s request. There is no universal Orthodox practice. Orthodox women’s groups and several synods have expressed concern that the “practices and prayers do not properly express the theology of the church regarding the dignity of God’s creation of woman and her redemption in Christ Jesus.”[1] There is a call for the Orthodox Church to clarify meaning and practice.

So what is really happening when a woman is Churched? Why do the Churching prayers talk about the mother’s impurity and sin? By considering the history of the Churching of Women we can see three ways this controversial language of impurity and sin has been understood: as part of what it means to give birth (ontological), as a way to understand ourselves (pedagogical), or in light of the coming reign of Christ (eschatological).

A Little Background

The wording in question is found in these two prayers:

O Lord God Almighty, the Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who by thy word hast created all things, both men endowed with speech and dumb animals, and hast brought all things from nothingness into being, we pray and implore thee: Thou hast saved this thy servant, N., by thy will. Purify her, therefore, from all sin and from every uncleanness, as she now draweth unto thy holy Church; and make her worthy to partake, uncondemned, of thy Holy Mysteries.

And:

O Lord our God, who didst come for the redemption of the human race, come thou also upon thy servant, N., and grant unto her, through the prayers of thine honourable Priest, entrance into the temple of thy glory. Wash away her bodily uncleanness, and the stains of her soul, in the fulfilling of the forty days. Make her worthy of the communion of thy holy Body and of thy Blood.[2]

These prayers have roots in two biblical passages: Leviticus 12:2b-8 and Luke 2:22-24. The Leviticus passage gives instructions about how long a woman is considered unclean after giving birth: 40 days for a male child and 80 days for a female child. She is to offer sacrifices and then she will be considered ritually clean. In Luke 2, the Theotokos brings the infant Christ to the temple and offers sacrifices. The first passage offers straightforward instructions and the other recalls an historical event. Neither however, says what childbirth impurity means, only what was done about it. No other biblical birth narrative mentions purification and so we are left with open questions about interpretation.

Ontological View – Giving Birth Creates Ritual Impurity

One of the primary ways this has been interpreted is ontologically, that as in the ritual tradition of Leviticus, giving birth creates a condition of ceremonial uncleanness in the woman’s body. This has nothing to do with bacteria or disease, which is what we often think of when we hear the word “unclean.” Instead, biblical laws about ritual uncleanness have to do with confusion of categories or crossing prescribed boundaries. Other examples of biblical uncleanness are eating unclean animals or touching dead bodies. Giving birth is a time of physical and spiritual border-crossing. Many traditional societies have similar types of taboos, created to preserve cultural or religious purity.

Ritual impurity in the Old Testament law is also separate from sin; it did not always mean the person had done something wrong. Occasionally, however, the words “impure” or “unclean” are used as a metaphor for sin, as in Isaiah 64:6. This causes confusion and in many New Testament letters we also see these words used to mean sin directly, as in Colossians 3:5 – “Put to death whatever belongs to your earthly nature: sexual immorality, impurity, lust, evil desires and greed, which is idolatry.”[3] In the first few Christian centuries, this understanding was further complicated by the fact that Greco-Roman culture had its own set of traditions of ritual impurity, including rules regarding menstruation and childbirth, similar to those found in the Jewish law. Greek writers also continued to use impurity language as a metaphor for sin. An ontological understanding of impurity can be seen in some Patristic writings, such as the Canons of Hippolytus which echo the Leviticus prohibition of staying away from church (40 days for a boy, 80 days for a girl). These canons give additional prohibitions for midwives to stay away for specified periods after assisting with births. If either new mothers or midwives came to church before the allotted time, they were to be seated “with the catechumens who have not yet been judged worthy to be accepted.”[4] This seems to suggest these women are, at least symbolically, excluded from the Faithful for the specified time.

The seventh century Pope Gregory the Great seems more sympathetic and yet offers a mixed reply to the English Archbishop Augustine who asked about menstruating women taking Communion. He wrote that women should not be forbidden to go to church or take Communion “But when a woman does not dare, because of her great reverence, to go there, she is to be praised.”[5] This ‘yes/no’ response is confusing and menstruating women and new mothers are left to decide between not going to church (even though Gregory says they may) or risking being thought impious for attending.

Some Orthodox may recognize these mixed messages from their own parishes. For women, the current rules regarding menstruation and new mothers can vary widely—anywhere from no restrictions at all to not touching holy things like candles or prosphora to not being able to enter a church. In 1980 The Orthodox Church in America condemned the barring of menstruating women from communion, but interpretation of the canons regarding women who have given birth remains with individual bishops and priests.

This issue can be particularly surprising for Western converts to Orthodoxy and its imbalanced application ensure an uneven range of experiences for women. An example can be found in an online forum where an Antiochian mother asks if a woman can be Churched at 38 days if it means she could attend, and receive Communion at, Pascha. The answers to her posted question are varied with some saying their priest Churched them early while others expressing their disappointment under similar circumstances. Clearly these people are in parishes where this is a very current question, not just something limited to traditionally Orthodox countries or a specific time in history.

Pedagogical View—Giving Birth Teaches Us About Ourselves

Another way of interpreting the language of sin and impurity in the Churching prayers is to see it as a way to come to terms with our own human sinfulness and failure. Alexander Schmemann suggests that by explaining the liturgical prayers for new mothers properly, they can be used without changes to teach us about ourselves.[6] He writes that, ‘…the very categories of the “pure” and the “impure,” which are indeed central before Christ, are radically transformed by Christ’s coming – transformed and not simply abolished…once this ultimate meaning is revealed in Christ, the old distinction is revealed to be not “ontological” but “pedagogical,” to be the means of leading man into the mystery of redemption.”[7]

The Churching prayers have a universal quality and recall penitential language found in most Orthodox services (‘Lord, have mercy!’). The language of the Churching prayers can also be seen in what the priest prays for himself at the start of Baptism, “And wash away the vileness of my body, and the pollution of my soul. And sanctify me wholly…”[8] This cleansing, this forgiveness, is something that all people need, as Orthodox liturgy states clearly and frequently. This liturgical reality should be taught in parishes in the context of Churching of Women as well.

Many contemporary mothers and priests approach the Churching prayers in this pedagogical manner. The 40 days away can be seen as a freedom. Matushka Jenny Schroedel wrote an article called “Forty Days with Natalie” about the goodness of the time apart and how Orthodox mothers “spend those days bonding with their newborn, healing and adjusting to the awesome responsibility of caring for the child.”[9] When asked further by email about the sin and impurity in the Churching prayers, Schroedel wrote,

After giving birth to my children, I liked those prayers that talked about my own sinfulness. I know that sounds strange. But it was such an awesome experience in both cases, and I could see so clearly my own sins and failings, I was terrified by my weakness, as many parents are. These prayers speak to that increased awareness that comes after such a profound and transformative experience. I welcomed these prayers…because I could see myself more clearly. I knew I needed a lot of help.[10]

These observations are honest and admirable. A 40-day period has undeniably positive features and many cultures can attest to the goodness of a time set apart for mother-child bonding. It must be admitted, however, that this is a newer interpretation, as bonding is not a concern of either the biblical writers or the Church Fathers.[11] It provides a new way to address ritual impurity, but doesn’t answer the ontological concerns about what ritual impurity means.

Eschatological View—Purity in Light of Eternity

A final interpretation of the language of sin and impurity is to consider it eschatologically – to judge it by its heavenly implications. This way of looking at Churching finds support in some Patristic writings and Scripture, but also in the liturgy of The Meeting of Our Lord and God and Saviour Jesus Christ.

The 4th century Didascalia Apostolorum discusses the freedom of Christians from the Jewish law, including menstrual and birth impurity. The author writes that since the Holy Spirit lives within all baptized Christians, women are no long subject to ritual purity rules that would have kept them from worship in the past. The author of the Didascalia writes,

For if the Holy Spirit is in thee, why dost thou keep thyself from approaching to the works of the Holy Spirit?...Wherefore, beloved, flee and avoid such observances: for you have received release, that you should no more bind yourselves; and do not load yourselves again with that which our Lord and Saviour has lifted from you. And do not observe these things, nor think them uncleanness; and do not refrain yourselves on their account, nor seek after sprinklings, or baptisms, or purification for these things.[12]

This sounds like the words of Romans 8:1-2, “Therefore, there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus, because through Christ Jesus the law of the Spirit of life set me free from the law of sin and death.” The Apostle Paul and the Didascalia do not simply ignore Jewish purity laws and any Christian continuation of them. Demetrios Passakos suggests that Paul has a “firm position against any attempt to relativize the new ‘in Christ’ situation with the acceptance of provisions of the old Law.”[13] In other Epistles, Paul uses this same reasoning against circumcision (in Galatians) and against special festivals and rituals (Colossians). “These are all destined to perish with use,” Paul writes, “because they are based on human commands and teachings.”[14]

What then shall we do? Turning in a new direction, Paul instructs the Colossians:

So if you have been raised with Christ, seek the things that are above, where Christ is, seated at the right hand of God. Set your minds on things that are above, not on things that are on earth, for you have died, and your life is hidden with Christ in God. When Christ who is your life is revealed, then you also will be revealed with him in glory.[15]

Here is our eschatological direction to guide our thinking about the Law. More clues are found in the Gospels where Christ is shown to heal and touch those with ritual impurity: lepers, Gentiles, demoniacs, the dead and, most interesting for us, the woman who had suffered from a hemorrhage for twelve years. Passakos suggests that Christ’s main concern was to not shut people out, “but rather to facilitate their access to God.”[16]

The liturgy for February 2, The Meeting of Our Lord and God and Saviour Jesus Christ, can also help us understand the new access we have to God through Christ.[17] Although Luke 2 describes this event as “the time of purification,” the liturgy makes no reference to it specifically. One troparion by John the Monk in Great Vespers, however, makes a reference to purity law:

Today He who once gave the Law to Moses on Sinai submits Himself to the ordinances of the Law, in His compassion becoming for our sakes as we are. Now the God of purity as a holy child has opened a pure womb, and as God He is brought as an offering to Himself, setting us free from the curse of the Law and granting light to our souls.[18]

The liturgy’s epistle reading from Hebrews also reminds us, “for the law made nothing perfect; there is, on the other hand, the introduction of a better hope, through which we approach God.”[19]

This “better hope” cannot be found through observance of the Law. Vassa Larin even suggests that the practice of ritual purity for menstruating women and new mothers is a “depreciation of the incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ and its salvific consequences.”[20] We all have pasts marred by sin and various types of impurity, but as Paul reminds us in 1 Corinthians 6:11, “this is what some of you were. But you were washed, you were sanctified, you were justified in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ and by the Spirit of our God.” Our new identity of relating to God in the Holy Spirit has begun. When considered alongside the Orthodox doctrine of theosis, the believer is further encouraged to orient him or herself to the path that leads toward God and transformation, as Romans 8:29 says, God predestined us “to be conformed to the likeness of his Son.” This calls for continual renewal, both of the individual and the Church as a whole.

Conclusion

Throughout Church history, various ways have been found to understand the language of sin and impurity in the prayers for the Churching of Women: ontologically, pedagogically and eschatologically. Today there are some who keep to ritual purity traditions and say women must be Churched and others who ignore the practice. Since the current use and interpretation varies so widely, now might be a good time for various Holy Synods to re-evaluate the Churching of Women and give direction and clarification for the sake of all.

What should not be lost, however, is the goodness of prayer and thanksgiving in celebration of new life and the generous co-operation with God in birth-giving. The handling of purity law in the New Testament and in writings like the Didascalia lend clear support to these themes already present in Orthodox liturgy. Perhaps fathers of new babies could also be included in some way. More education and study is needed to clarify what is meant by Churching, and not simply to be ignored by those who find the language uncomfortable. And most importantly, the Church needs to focus on the eschatological implications of the Churching of Women and celebrate it in the true spirit of freedom offered in Christ, so that, as Ephesians 4:15 says, “speaking the truth in love, we will in all things grow up into him who is the Head, that is, Christ.”

In this spirit of expectancy from the Lord, let us return to the visual image with which the discussion began—that of a mother with a baby in her arms standing at the back of the church, waiting for the priest. On one level, she seemed like just a typical mother, and yet, as she faced into the church, there was a resonance between that woman and that child and another woman and another child seen on the iconostasis and on the sanctuary asp—the Theotokos, with Christ in her arms. What is best about the Churching of Women is found in this moment, where, as Schmemann writes,

the Church, in her prayers, unites those two motherhoods, fills human motherhood with the unique joy and fullness of Mary’s divine Motherhood…and it is this grace…that each mother receives yet also gives as she brings her child to God.[21]

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barkley, Gary Wayne, trans. 1990. Homilies on Leviticus: 1-16 /Origen. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press.

Bradshaw, Paul F., ed. Carol Bebawi, trans. 1987. The Canons of Hippolytus. Bramcote: Grove Liturgical Study.

De Troyer, Kristin, ed. 2003. Wholly Blood, Holy Woman; a Feminist Critique of Purity and Impurity. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press.

Didascalia Apostolorum—http://www.bombaxo.com/didascalia.html

FitzGerald, Kyruaki Karidoyanes, ed. 1999. Orthodox Women Speak; Discerning the ‘Signs of the Times’. Brookline, MA: WCC Publications/Holy Cross Orthodox Press.

FitzGerald, Kyruaki Karidoyanes. 1998. Women Deacons in the Orthodox Church; Called to Holiness and Ministry. Brookline, MA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press.

Fonrobert, Charlotte Elisheva. 2000. Menstrual Purity; Rabbinic and Christian Reconstructions of Biblical Gender. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Hapgood, Isabel. 1996. Service Book of the Holy-Orthodox Catholic Apostolic Church. Englewood, NJ: Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese.

Larin, Vassa. 2008. “What is ‘Ritual Im/Purity and Why?’ St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly. 52:3-4.

Monachos.net http://www.monachos.net/forum/showthread.php?t=4925.

Mother Mary and Kallistos Ware, trans. 1998. The Festal Menaion. South Canaan, PA: St. Tikhon’s Press.

Passakos, Demetrios. 2002. “Clean and Unclean in the New Testament: Implications for Contemporary Liturgical Practices.” Greek Orthodox Theological Review. 47:1-4.

Ranke-Heinimann, Uta. Trans. Peter Heinegg. 1991. Eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven; The Catholic Church and Sexuality. New York: Penguin Books.

Schmemann, Alexander. 1976. Of Water and the Spirit. London: SPCK.

Schroedel, Jenny. “Forty Days With Natalie” Published on Boundless.org on January 25, 2007. www.boundless.org/2005/articles/a0001435.cfm

Kathryn Wehr, MCS, (Master of Christian Studies, Regent College, Canada) is from Minnesota and is a post-graduate student at the Institute for Orthodox Christian Studies in Cambridge, England (www.iocs.cam.ac.uk). Her areas of research are Pastoral Theology and Theology and the Arts. She is also a folk musician and her music can be found on iTunes or at www.katywehr.com.

©2010 Kathryn Wehr. From Orthodoxy Today. Used with permission.