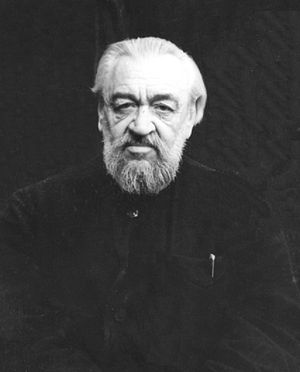

Fifty years ago, on November 4, 2012, Metropolitan Nestor (Anisimov) departed to the Lord. He was one of the greatest missionaries of the twentieth century, the enlightener of Kamchatka, a humble archpastor, who spent eight years in the Mordovian gulag for his faith in Christ. Pravoslavie.ru/OrthoChristian.com is publishing these notes about this remarkable man, sent to us by his Godson, Alexander Kirillovich Karaulov.

Metropolitan Nestor (Nicholai Alexandrovich Anisimov) was born in Vyatka on November 9/22, 1885, on the feast of icon of the Mother of God, “She Who is Quick to Hear”. From his earliest childhood years he stood out for his deep religiosity.

After graduating from secondary school he entered the missionary courses given at the Kazan Theological Academy.

In 1907, feeling a yearning in his soul and the will of God, and having received a blessing from the holy and righteous Father John of Kronstadt, Nicholai Anisimov resolved to take up the difficult labor of a missionary. On April 17, 1907, in the Kazan Monastery of the Transfiguration of the Savior, he received the monastic tonsure and was given the name Nestor. On May 6 of the same year he was ordained a hieordeacon, and three days later, a hieromonk.

On June 2, 1907, Fr. Nestor left for the land of his missionary service—Kamchatka. For two years, Hieromonk Nestor conscientiously fulfilled his pastoral duties under severe weather conditions, often risking his life to preach the word of God and convert thousands of pagan Kamchadals to Christ. His deep respect for the people, their language, and traditions, his constant readiness to help the sick, infirm, and downtrodden won Hieromonk Nestor the ardent love and trust of a flock living in the furthermost corners of an enormous region. Just the same, the young pastor did not feel fully gratified with his own activities. He understood that his small labors would never be enough to resolve the problems inherent in a Kamchatka forgotten by all. He needed to draw the attention of the powerful of this world, the clergy, and all honest people who wished to help their neighbor suffering from poverty, sickness, drunkenness, ignorance, and the self-will of their local petty tyrants. Thus was the idea born of creating the Orthodox Beneficent Brotherhood of Kamchatka.

Hieromonk Nestor (Anisimov), Missionary to Kamchatka. Photo 1907.

Hieromonk Nestor (Anisimov), Missionary to Kamchatka. Photo 1907.

In 1910-17, a massive number of churches, chapels, schools, orphanages, hospitals, and clinics were built with funds from the Brotherhood.

Having learned the Tungus (Evenky) and Koryazh languages, Hieromonk Nestor translated the Divine Liturgy, a portion of the Gospels, and various prayers into those languages. For his labors Fr. Nestor was raised to the rank of Igumen in 1913. Even then, he was already being deservedly called the “apostle of Kamchatka”.

When World War I broke out, Fr. Nestor organized and headed a medical division called “First aid under enemy fire.” As a member of the Life Guards of the Dragunsky regiment, he accompanied the soldiers in cavalry attacks on horseback, personally carried the wounded from the field of battle, bandaged them, comforted them, and organized their transfer to military hospitals. For his pastoral mercy, his outstanding fearlessness and bravery, Igumen Nestor was given the highest military award ever granted to the clergy—a pectoral cross on the ribbon of St. George, as well as a number of military awards with swords and ribbons (St. Anna, 2nd and 3rd degrees, and St. Vladimir, 4th degree).

At the end of the year 1915, Fr. Nestor was called from the front and raised to the rank of Archimandrite. He again set out for Kamchatka to continue his pastoral mission.

On October 16, 1916, Fr. Nestor was consecrated a bishop and appointed as head of the newly-created diocese of Kamchatka. Bishop Nestor called his time in Kamchatka the happiest years of his life.

Bishop Nestor was one of the few hierarchs who did not accept the February revolution, as he considered it to be the plot of Russia’s enemies. In 1917–18 he participated in the All-Russian Local Council and the election of the holy Patriarch Tikhon. After the Bolshevik revolution, during the heat of the October revolutionary events in Moscow, Bishop Nestor walked through the city at night with a medical bag, and, disregarding all danger, gathered the wounded and gave them medical aid. At the blessing of the Council, as the member of a commission for photographing and describing the damage caused to the Kremlin Cathedral by the Bolsheviks, Bishop Nestor published a scathing exposé entitled, The Shooting of the Moscow Kremlin, which has been recognized as one of the most important documents of that era. During that same period Bishop Nestor became the inspirer and organizer of the only sincere attempt (unfortunately, unsuccessful) to save the Royal Family. In March of 1918, the bishop was arrested for the first time by the Bolsheviks and was in prison for nearly a month. He was released only due to pressure from the Local Council and of the faithful. All of Orthodox Moscow came to the defense of the young archpastor.

After the Council closed, Bishop Nestor made his way with the utmost difficulty—through Kiev, Odessa, the Crimea, Turkey, Syria, Egypt, India, and China—to Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, where he continued his episcopal service. Soon, however, the Bolsheviks banished him from Kamchatka.

Finding himself in forced emigration in Harbin, Manchuria, Bishop Nestor was deeply distressed by his separation from his beloved homeland, but he did not fall into despondency. With redoubled energy he continued his pastoral, ascetic, compassionate, social activities and soon became one of the accepted spiritual leaders of the far-eastern branch of the Russian emigration. In 1921, Bishop Nestor founded the Harbin Kamchatka podvorye, (representation), and later the House of Mercy and Industry, thanks to which the lives were saved of thousands of adults and children swept into the maelstrom of civil war. Through the bishop’s efforts, a church and memorial chapel dedicated to the Royal Martyrs were built on the territory of the House of Mercy.

Despite the confusion inherent in Church life of the 1920s–30s, both in the homeland and the Russian diaspora, Bishop Nestor consistently stood for the idea of unity with the suffering Mother Church. During this period, he visited a number of countries in Europe and Asia, met with hierarchs of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad, representatives of various Local Orthodox Churches, and many distinguished figures of the Russian emigration. He also made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. In 1938–39, Bishop Nestor performed missionary work in India and Ceylon (Sri-Lanka).

In 1933, he was raised to the rank on Archbishop, and in 1941 he was granted the right to wear a cross on his klobuk.

Bishop Nestor was never deceived about the nature of the Bolshevik regime in Russia. He clearly exposed its anti-theist nature in October 1917, having observed the tragic events surrounding the storm of the Moscow Kremlin by the Bolsheviks. His active participation in many events of the civil war in the Ukraine, the Crimea, Siberia, and the Far East also left no doubt in his mind. Ever consistent in his views, Bishop Nestor always openly expressed his negative attitude toward the Bolshevik regime, both in his speech and in his many books, brochures, and articles. A conviction that the anti-theistic government would inevitably fall never left Bishop Nestor to the end of his days.

Nevertheless, he always remained an ardent patriot of his Motherland, and a staunch fighter for the unity of the Russian Orthodox Church. When World War II broke out, Bishop Nestor decided that he had no right to remain outside the Mother Church during his Motherland’s time of heavy trial. In 1943, the most difficult time for Russia, when no one could foresee the outcome of the war, he secretly renewed his contact with the Moscow Patriarchate. For a specific period of time he had to hide these contacts, because under the extremely cruel conditions of the Japanese occupation they posed a mortal threat to the bishop as well as his flock. Even so, Bishop Nestor’s sermons rang out with renewed strength about the sacred duty of defending the Fatherland from its would-be enslavers, and this message drew vital support from his parishioners.

In June of 1945, even before the beginning of the USSR’s military action against Japan, Bishop Nestor took a step that was, considering the current conditions, not only bold, but also truly heroic—he openly commemorated the name of His Holiness the Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia at the Divine services. At his initiative, all the hierarchs of Harbin signed a petition to the Patriarch of Moscow to accept their flock under his omophorion.

In August of 1945, Archbishop Nestor along with other Russians in Manchuria rejoiced at the coming of the liberating army and met with its commanders.

In 1946, His Holiness Patriarch Alexy I raised Bishop Nestor to the rank of Metropolitan, and appointed him as ruling hierarch of Harbin and Manchuria, a Patriarchal Exarchate in East Asia. The bishop’s activities in this capacity during the difficult post-war years was exceedingly fruitful.

Metropolitan Nestor (prisoner Nicholas Anisimov) in Dubravlag. Photo1955.

Metropolitan Nestor (prisoner Nicholas Anisimov) in Dubravlag. Photo1955.

After he was freed in 1956, Nestor was appointed Metropolitan of Novosibirsk and Barnaul. This was the largest diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church, which at that time included the territory of Novosibirsk, Tomsk, and Kemerovo provinces, the Krasnoyarsk and Altai lands, as well as the Republic of Tuva (in all about 20% of the territory of the USSR).

Weighed down by numerous illnesses and half blind, Metropolitan Nestor found the strength to preach the world of God not only in the largest cities of the diocese (Novosibirsk, Krasnoyarsk, Tomsk, Kemerovo, Barnaul, Biisk, Kyzyl, and Achinsk), but even in the lost backwoods and villages, where, as he himself put it, no bishop had ever step foot, and people had never seen a bishop serving. This led to a noticeable invigoration of Church life in the diocese. Met. Nestor protested against the closing of churches, and raised the question of opening new parishes and theological seminaries. His heightened activity evoked the authorities’ extreme displeasure, and new persecutions were organized against the archpastor.

In December 1958, Met. Nestor was appointed as ruling hierarch of the Kirovograd and Nicholaevsk diocese. During this period, regardless of ongoing persecutions, Met. Nestor continued to travel throughout the diocese, celebrate the Divine services, preach the word of God, and protest against the closing of churches by the God-hating authorities. During the difficult time leading up to the closure of the Dormition Kiev-Caves Lavra, Met. Nestor visited the monastery to comfort its abbot and brothers, and to strengthen them in the conviction that the Christian faith would inevitably prevail.

In 1961, Met. Nestor completed a remarkably sincere book of his memoirs, which have been reprinted numerous times in recent years.

Metropolitan Nestor reposed on October 22/November 4, 1962, in Moscow, on the day the Church celebrates the Kazan icon of the Mother of God. The prayer of absolution at his funeral service was read by His Holiness Patriarch Alexy I. Met. Nestor was buried in the yard of the Transfiguration Church of the Patriarchal residence in the Moscow suburb of Peredelkino.

Orthodox Christians continue to remember thankfully this great missionary, the humble man of prayer, merciful pastor, ardent patriot, brilliant preacher, outstanding religious writer, and simply remarkable human being.

The diocese of Kamchatka has petitioned the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church to canonize the enlightener of the peoples of Kamchatka, Metropolitan Nestor.

O Lord, remember Thy hierarchs in Thy Kingdom!