See The Crucifixion of Christ, Part 1b. The Lamb of God

This is now part 2 on the Crucifixion, about the seven last statements made by Christ. He said very little from the Cross because of the lack of oxygen. The inability to get a good breath made it very difficult to speak at all.

The differences in the four Evangelists on the Crucifixion

Each of the four Evangelists tells the story of the Crucifixion a little differently according to the particular themes of their Gospels. Sometimes, for example, one says Christ cried out but doesn’t say what He said, whereas another evangelist tells us what He said. The Gospels are not identical. Each Gospel has a specific author, an audience, themes, interests, etc. So they choose to include or exclude those details that emphasize their particular message or their portrayal of Christ. For example, Mark’s emphasis, one of his big themes, is the idea of Christ as the Suffering Servant. And in Matthew we have one of his main themes, the fulfilment of prophecy. So in both Matthew and Mark we have Christ saying from the Cross something that both shows Him to be fulfilling prophecy and to be the Suffering Servant of Isaiah 53, and that is the words: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” which we will discuss momentarily. That line indicates, as I said, fulfillment of prophecy.

Luke’s Gospel has as one of its main themes repentance and forgiveness. It is Luke’s Gospel that has such parables as the Prodigal Son, the conversion of Zacchaeus, and the Publican and the Pharisee. So in Luke’s Gospel we have three statements by Christ, and two of them have to do with forgiveness: The repentant thief and also Christ forgiving those who crucified Him. He also has the statement about the Spirit, “Into your hands I commit my spirit,” because the Spirit is another important theme in Luke’s Gospel.

Then, finally, the last three statements are found in the Gospel of John, which not only emphasizes the divinity of Christ but also emphasizes the reality of His human nature. So there we have two statements reminding us that Christ was human: “I thirst,” and also the reference to His mother “Mother, behold your son. Son, behold your mother,” which also tells us something about her relationship to the Evangelist who preserved these comments for us. And finally in the Gospel of John we have the last words, and that is, “It is finished,” because another one of John’s themes is an emphasis on Christ doing all things according to the will and the plan of the Father.

So you mustn’t be surprised or disturbed by the fact that all of the Gospels do not include all details, or that they relate this story or other stories slightly differently. The Gospels were not intended to be a newspaper account. They weren’t intended to be an unbiased historical account. They contain history, but they were a theological presentation, and the Evangelists felt free to include or exclude the details that either supported or detracted from their particular portrayal of Christ, because each of them emphasized something special about the person of Christ. This doesn’t mean that they were dishonest. It just means that they wrote their accounts in a way that was different from how we might write something today. Today, when we write history we try to include everything relevant, we try to be unbiased and we try to present everything we can possibly think of, all conceivable angles. But they didn’t write like that, even in ancient history. And the Gospels are not history. The Gospels are theology and history together. We will discuss this more when get into our introduction on the Bible and we arrive at the Gospels.

“My God, my God, why hast Thou forsaken me?”

Now let’s take that first statement, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” St. John Chrysostom notes that by this statement Christ is not expressing agony or a sense of abandonment by God or despair, but that He was quoting the Scriptures. Many people know this, but still many—it’s surprising how many—think that because of this statement Christ was in despair on the cross. That is not correct.

The words, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” come from Psalm 22. The words are the first line of Psalm 22. Now, the Jews did not number the psalms. They were the hymns of the Jewish people, and at this time the Bible didn’t have any chapters or verses. In order to ask people in the synagogue to sing a particular hymn, they would say, “Let us all sing, ‘The Lord is my Shepherd’,” or “Please sing, ‘My God, My God, Why Have You Forsaken Me?’” People knew these psalms by heart, but they weren’t numbered. The title of the psalm was the first few words, just like the titles of our hymns are the first few words of that hymn. St. John Chrysostom knows this, and he also testifies to the fact that Christ calling upon God is a way of honoring God. So here’s what Chrysostom says: “He said this that unto His last breath they might see that He honors His Father and is in no way an adversary of God. Wherefore also He uttered a certain cry from the prophet [he’s referring here to David in the psalms] that even unto His last hour bearing witness to the Old Testament.” So why did Christ quote this first line of Psalm 22? Because it was indeed fulfillment of prophecy. If you have never read this psalm, you must read it. It contains so many elements of what was happening to Christ on the cross. It talks about them piercing His hands and His feet, about them gambling for His clothes, people surrounding Him, staring at Him and gloating over Him, etc. But what is significant is not simply that it is fulfillment of prophecy, or that Christ was hanging on the cross and that His crucifixion scene mirrored that of the psalm, the prophetic psalm, but that the psalm ends in the glorification of God. The last third of the psalm is a statement of glory and praise of God. Isn’t that remarkable? It begins as a psalm of lament, but it changes and becomes a psalm of praise and glorification of God; as though the Lord were saying, “It may look bad now, but in the end I will be vindicated”; because He knew that He would rise from the dead.

Now let’s mention one other aspect of this concept, that Christ saying, “My God, my God why have you forsaken me,” wasn’t an expression of fear in Christ. The Fathers do discuss the fear shown by Christ, but they usually talk about that in the context of the agony in the garden of Gethsemane. They agree that by the time Christ was on the cross He was not in fear. He did have a natural fear, which He expressed in the garden when He asked the Father to take that cup away from Him. The Fathers believe that this was entirely natural. It was due to the human nature of Christ by which, according to our nature, we try to preserve our life. And many of the Fathers talk about this as a very natural component of all created things—that even animals, which do not even have a knowledge of death—they’ve never experienced death because they’re alive—don’t comprehend such things. Yet when they are threatened they try to preserve their life, they run away. This is part of our nature—so it was not a sin for Christ to have a desire to preserve His life.

Chrysostom says about this and about his statement on the cross, “My God, my God…” and all the other things that happened, that the Lord was not in fear, but very, very calm while He was on the cross, that He did everything quite deliberately. Here are Chrysostom’s comments on that: “Note how He did everything with calmness, even though crucified; speaking to the disciple about His mother, fulfilling prophecies, holding out to the thief fair hopes for the future. Yet before being crucified, He was observed to be sweating and in an agony, fearful. Why in the world was this? For in that time before the frailty of His human nature was demonstrated, whereas here the infinite extent of His power was being shown. Besides, He was giving us instruction in both cases, that, even if we are greatly perturbed in anticipation of keen sufferings, not on that account to refuse to accept suffering; but when we actually enter upon our trial then everything will be thought very easy and not hard to bear. Let us not then tremble at the thought of death. We must carefully keep to the middle course, neither going to meet death by our own hand even if we are enduring trials without limit, nor on the other hand drawing back and shrinking away when drawn to sufferings willed by God.”

The Gospel of Luke: forgiveness.

Luke’s Gospel is the one that has the forgiveness statements—so what about the statement, “Father forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing”? St. Augustine said this about that: “Even while He was being killed, the doctor was curing the sick with His blood. He said, you see, ‘Father, forgive them for they do not know what they are doing.’ Nor were these words futile or without effect; and of those people, thousands later on believed in the one they had slain, so that they learned how to suffer for Him who had suffered both for them and at their hands.” And those thousands who later believed, of course, were the Jews who believed after Pentecost—they were the first members of the Church.

“Today thou shalt be with me in paradise.”

Now about the statement to the thief, “Today you will be with me in Paradise.” Many times in the Orthodox Church we remember the salvation of the thief on the cross, how he was the first to enter Paradise, how he was saved in an instant, and we remember his repentance in one of our most commonly sung Communion hymns when we repeat the words of the thief: “Remember me, O Lord, when you come into your Kingdom.” There is, of course, so much that could be said about this from a perspective of repentance and forgiveness, but we’ll have to leave that for another time. Now I want to share with you something interesting that Augustine saw in this statement. He saw in the different behavior and the treatment of the two thieves a foreshadowing of the future judgment of us all. The one thief reviled Christ, even as he himself was being crucified, while the other said “Remember me, O Lord, in your kingdom.” So here’s St. Augustine: “The cross itself, if you consider it well, was a judgment seat; for the judge being set up in the middle, the one thief who believed was delivered, the other who reviled was condemned. Already He signified what He is to do with the quick and the dead. Some he will set on his right hand and others on His left. That thief was like those who shall be on the right hand, the other like those that shall be on the left.”

“Woman, behold thy son.”

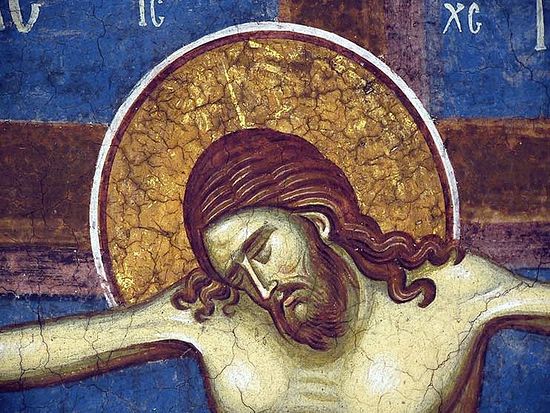

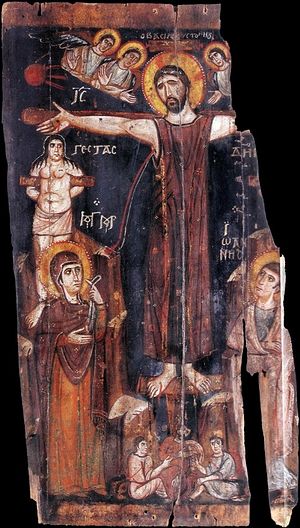

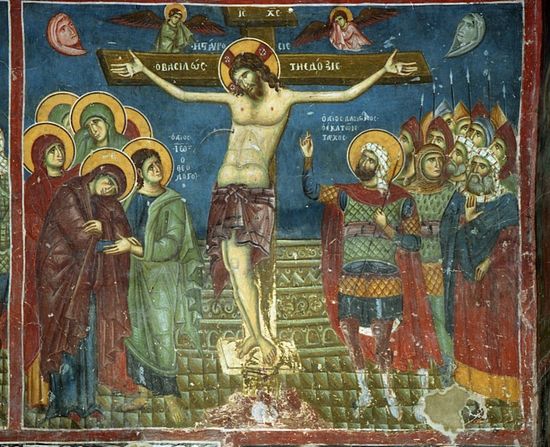

Holy and Great Friday. The Crucifixion. Fresco in the Church of St. Nicholas in Prilepe, Macadonia. 11th-13th c.

Holy and Great Friday. The Crucifixion. Fresco in the Church of St. Nicholas in Prilepe, Macadonia. 11th-13th c. So, St. Luke’s Gospel has two statements on forgiveness, and also the statement, “Into your hands I commit my spirit.” John’s Gospel has the statements, “I thirst,” “It is finished,” and “Woman, behold your son,” Now this is a very interesting factor about the Crucifixion—that the Lord remembered His mother. She was standing by the cross, and in His last moments He took care to make sure that she would be cared for. I know that there is some debate [among Protestants.—O.C.] about whether or not the Theotokos had other children, whether she was ever-virgin, because the Gospels tell about other children: “the brothers and sisters of the Lord,” for example. Now in my opinion this statement of Christ on the Cross, handing His mother over to the care of the Beloved Disciple is absolutely the best proof that the Theotokos had no other children. She was, by now, a widow. He was her only son, and if He did not find someone to care for her she would be left destitute. This is what happened to widows. There was no such thing as social security or food stamps or welfare or any programs to care for elderly people, so the predicament of widows was a very, very grave one. It was very tragic to be a widow with no children. If she had other children of her own they would have taken care of her, there would have been no need for Christ to hand His mother over to the care of the Beloved Disciple. You can see that it wouldn’t make sense, if she had other children, that she would be given over to St. John to take care of her. So, I think that this is extremely strong evidence that she had no other children. The children of Joseph, “the brothers and sisters of the Lord,” basically the step brothers and sisters of Christ, had no obligation to take care of her. She was not their mother.

Here is what Chrysostom says about the fact that the Lord remembered His mother on the cross: “While crucified, He gave His mother to his disciple’s keeping to instruct us to take every care of our parents, even to our last breath. Why was it that He made no mention of any other woman, though others also were standing there? To teach us to give more to our mothers than to any others. For just as we must not even recognize parents who act as an obstacle to us in spiritual affairs, so also when they do not hinder us in any way we must give them everything that is their due and place them ahead of all others in return for their bringing us into existence, in return for their care of us, in return for the numberless ways in which they have helped us.” St. Augustine also had a comment on this. Here’s what he said: “That on the cross He acknowledged His mother and entrusted her to the Beloved Disciple, aptly indicated His human affection at the time when He was dying as a man. The hour had not yet arrived when, as He was about to turn water into wine, He had said to the same mother ‘What have you to do with me? My hour has not yet come.’ You see? He had not received from Mary the power He had in His divinity, but He had received from Mary what was hanging on the cross.”

St. Ambrose, who was the bishop of Milan and another wonderful Latin Father, had some beautiful comments to make about Christ’s care of His mother on the cross and uses this to try to teach mothers about how to raise their children to be devoted to the Lord: “Mothers, wean your children. Love them, but pray for them that they may be long lived above the earth—not on it, but above it. Nothing is long-lived on this earth, and that which is long-lived is brief and more hazardous. Warn them rather to take up the Cross of the Lord than to love this life. Mary, the mother of the Lord stood at the cross. When the Apostles fled, she stood at the cross and with reverent gaze beheld her son’s wounds. For she awaited not her child’s death, but the world’s salvation. Jesus had no need of a helper for redeeming all, for He saved all without a helper. He received the devotion of His parent, but He did not seek another’s aid. Imitate her, holy mothers, who in her dearly loved only Son set forth such an example of motherly virtue. You do not have sweeter children, nor did the Virgin seek the consolation of being able to bear another son.” Isn’t that beautiful?

“I thirst.”

How about the statement, “After this, Jesus knowing that all things were accomplished, said ‘I thirst’,” and that He was given vinegar, as the Gospels say? Well, condemned people were given a kind of a sour wine. It was a cheap wine that had become vinegar, and the Gospels say that He was given this vinegar to drink. Sometimes it was mixed with gall or myrrh, which acted as a mild analgesic, a mild pain reliever similar to aspirin. This is kind of remarkable because it would hardly help to alleviate such terrible pain. Why Christ refuses to accept it after He tastes it has never been explained as far as I could find. Perhaps the Fathers explain it somewhere but I’ve never run across an explanation. I have my own theory, it’s just my own opinion, but I think that He may have refused to accept it because he tasted the gall and He didn’t want to accept any lessening of His pain. I think it may indicate the fact that He willingly accepted all of the pain of the cross, that He endured this for us without asking for any alleviation of His pain. That’s just my opinion, but I think it may be true.

Now what does Chrysostom have to say about the statement, “I thirst”? “The Evangelist endeavored in every way to show that this death was something new, if in fact every detail was controlled by the one who was dying, and that death did not enter His body until He Himself willed it, and He willed it only after all had been fulfilled. That is why He said, ‘I have the power to lay down my life, and I have the power to take it up again.’ Therefore, knowing that all things were now accomplished, He said ‘I thirst’, in this once again fulfilling a prophecy. Offering Him a sponge soaked in wine, they gave Him a drink in the way in which they offered it to condemned criminals. Therefore, when He had taken it, He said, ‘It is finished.’ Do you see that all things were done calmly and authoritatively?” Chrysostom also said: “What does that mean, ‘It is finished’? That the prophecy was fulfilled concerning Him.”

“It is finished.”

About the fact that the Lord bowed His head and gave up His spirit, and then as Luke tells us that when He gave up His spirit He said, “Into your hands I commend my spirit”—the Fathers say that this shows the giving up of His spirit at the time that He wished to give it up, that He was in control of His death. In other words, it shows Christ’s control over the events. Now this is what Chrysostom has to say: “It is not after bowing one’s head that one expires, ordinarily. Here however it was just the opposite. For it was not when He expired that He bowed His head, as is the case with us, but after He bowed His head, then He expired. By all these details the Evangelist made it clear that Christ Himself is Lord of all.” Do you understand his point here? He’s saying that ordinarily people die and then their head falls forward, but here Christ allowed His head to fall down and then He died; so it’s quite opposite and shows that He was in control. St. Augustine makes a very similar point: “This shows how He died not by necessity, but by His own power and authority, waiting until all that had been prophesied on His behalf had been accomplished. He handed over the spirit with humility, that is, with a bowed head. He would receive it back again by rising again with a head lifted up.”

How about the fact that the Lord cried out with a loud voice and gave up His spirit? Chrysostom said: “’I have the power to lay down my life, and I have the power to take it up again’, he said; and, ‘I lay it down of myself.’ So for this cause, He cried with the voice out loud, that it might be shown that the act is done with power. The centurion, for this reason, most of all believed because He died with power. This cry rent the veil and opened the tombs and made the house desolate.” The house, of course, that he is referring to is the Temple.

The veil of the temple was rent in twain.

Now about the fact that the curtain of the Temple was torn. St. John Chrysostom said this: “And He did this not as offering insult to the Temple—for how could He who said, ‘Make not my Father’s house a house of merchandise’?—but, declaring them to be unworthy of His abiding there, like as also when He delivered it over to the Babylonians. But not only for this was this thing done, but what took place was a prophecy of the coming desolation and a change to the greater and higher state, and as a sign of His might.”

So there Chrysostom is talking about how the destruction of the Temple by the Romans in the year 70, which Christ prophesied, was similar to how the Lord had allowed the first Temple to be destroyed by the Babylonians. And that, of course, this destruction by the Romans was a prophecy, and the veil of the Temple being rent by the cry of Christ was a prophecy of the coming desolation, that is, the coming destruction of the Temple by the Romans; and a “change to the greater and higher state” that Chrysostom is talking about, is a change from animal sacrifice to spiritual worship; because the Christians were the ones who did not participate in animal sacrifice. They always had spiritual worship.

St. Jerome said something interesting about the tearing of the curtain of the Temple. “The curtain of the Temple is torn, for that which is veiled in Judea is unveiled to all the nations. The curtain is torn, and the mysteries of the Law are revealed to all the faithful. But to the unbelievers, they are hidden to this very day.” I think there is something to what St. Jerome says also. There’s another meaning of the tearing of the curtain—that it opens up the Holy of Holies to everyone. It opens up that mystery, it’s unveiled and open to all. And this is something we remember: that by the Resurrection of Christ the Kingdom of Heaven is opened up to us. We remember this because for the 40 days after Pascha, the doors leading to the sanctuary in an Orthodox church are left open. We have three doors in the iconostasis. There is the middle door, the royal gate, which could also be closed off with a curtain at some points during the Divine Liturgy, and we also have the north door and the south door, or otherwise known as the deacon’s doors, the helper’s doors, those two side doors. These three doors are typically left open for 40 days after Pascha to show us that access to God is now available to us. Because of the Resurrection of Christ, the Kingdom of Heaven is open to us.

The dead shall be raised.

Now what about the detail in the Gospel of Matthew—that the bodies of the dead arose when Christ cried out? Here’s what St. John Chrysostom had to say about that: “And together with these things, He showed Himself also by what followed after these things, by the raising of the dead. By a voice He raised them, His body continuing up there on the cross; and they are not merely raised, but also, rocks are rent, and the earth shaken. They said, ‘He saved others, Himself he cannot save,’ but while abiding on the cross, He proved this most abundantly on the bodies of His servants. For if for Lazarus to rise on the fourth day, was a great thing, how much more for all those who had long ago fallen asleep, at once to appear alive, which was a sign of the future resurrection?” And about the detail that they appeared to many (that is, those who arose, who had been dead for a long time) Chrysostom says, that this happened “in order that what was done might not be accounted to be an imagination, they appear; even to many in the city.” So their appearance was like verification that in fact these things happened.

The people are moved to compunction

On the centurion’s statement, “Truly He was the Son of God,” and the crowd returning home beating their breasts, Chrysostom said: “So great was the power of the Crucified, that after so many mockings, scoffs and jeers, both the centurion was moved to compunction, and the people.”

More on crucifixion as a manner of execution.

After the Lord had died and they came to take Him down from the cross, the thieves were still alive, and it tells us that the Roman soldiers broke the legs of the thieves. Most people think that this was done in order to hasten death by causing internal bleeding, but that’s not the reason. This wouldn’t have hastened death all that much. Now, as I told you, crucifixion was a very slow death. The crucified person could hang on a cross for many days, depending upon how severe their scourging was. They usually died of suffocation or asphyxia, and their death was also hastened by shock, by exposure to the elements, etc. But as the person hung upon the cross, it was very difficult for them to breathe, and you could get a little bit of an idea of this if you simply stand up and try leaning forward, if you bend at the waist and put your arms outstretched to your side. Bend forward and see how much more difficult it is to breathe in that position, and then try standing upright with your back straight and you can see the difference. Now, in addition to the fact that the Lord was bent forward, the nails that would go through the wrists would sever certain nerves—it was very difficult for people hanging on a cross to get a good, deep breath. That’s why it was hard for them to speak; it was hard for the Lord even to say those seven things. In order to get a good breath, they had to sort of lift themselves upright by pressing their back against the cross, and in order to do that they had to put more pressure on their feet, which had nails in them. So the Lord had to push on His feet and push Himself upwards, which also strained the wrists and the nails in them. And with all of these nerves running through the wrists and the feet, the pain was terrible. Terrible pains radiated throughout the body, but this was necessary simply to breathe. Eventually, however, because it was so painful and so difficult to breathe, the carbon dioxide in the blood would build up because it was easier to inhale than exhale; the person couldn’t get rid of the carbon dioxide in their blood, and without enough oxygen the people eventually died of asphyxia. So, that is why the legs of the thieves were broken—so that they couldn’t step on their feet, lift themselves up and breathe. That is what caused their death, hastened their death, and within just a few minutes, they would die. The thieves had to be allowed to die before nightfall, because under Jewish law an executed man could not be left on the cross or hanging on a tree overnight, because it was considered a curse on the land to leave somebody dead or a dead body out overnight. They had to be buried quickly, because the Sabbath was about to begin at sunset.

If you want more information about the physical death of Christ, there is a very detailed article that was published in JAMA—that is, the Journal of the American Medical Association—called, “On the physical death of Christ.” It was published on March 21, 1986 and it’s been republished by many people. It caused quite a sensation because this is an actual, very highly respected medical journal. A couple of doctors wrote an analysis of what caused the death of Christ, and they talked about all of the physical aspects of crucifixion. It’s very technical, it talks about all of the different nerves and muscles, and there’s a lot of medical jargon involved; but if you’re interesting in knowing about this, you could look up that article.

The thieves’ legs were broken, but the Lord was pierced with a spear and out came blood and water, the Scriptures say. Here’s what Chrysostom has to say about that: “What could be more lawless, what could be more brutal than these men, who carried their madness to so great a length, offering insult even to a dead body? But mark how He made use of their wickedness for our salvation. For after the blow, the fountains of our salvation gushed forth from there.” And of course “the fountains of salvation,” are the blood and the water, uniformly recognized by the Fathers as symbolizing Communion and Baptism. Chrysostom also said: “For the very things they did for a wicked purpose, became powerful champions of truth. There was indeed a prophesy which said, ‘They will look upon Him whom they have pierced’. In addition to this, an ineffable mystery was also accomplished, for there came out blood and water. It was not accidentally or by chance that these streams came forth, but because the Church has been established from both of these. Her members know this, since they have come to birth by water and are nourished by Flesh and Blood.”

The JAMA article, by the way, about the physical death of Christ, tells us that probably what had happened there was when the solider pierced the side of the Lord, he pierced the sack around the heart, and that’s the reason that first the clear fluid came out, which is the fluid around the heart, and then the blood.

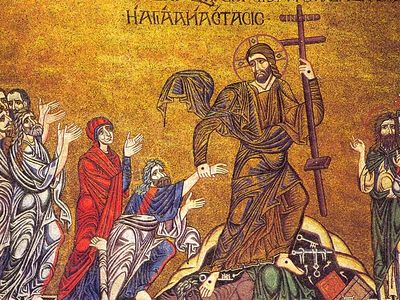

The icon of the Crucifixion.

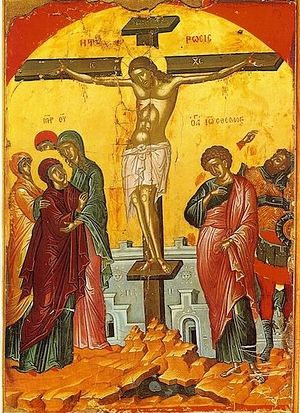

Orthodox icon of the Crucifixion of our Lord Jesus Christ, by Theophanis the Cretan (1535), Stavronikita Monastery, Mount Athos. Photo: Pinterest.com

Orthodox icon of the Crucifixion of our Lord Jesus Christ, by Theophanis the Cretan (1535), Stavronikita Monastery, Mount Athos. Photo: Pinterest.com So the hands of Christ are flat against the cross. They’re not clenched, even though because the nail Christ was in Christ’s wrist it would have naturally caused His hands to be clenched. But on the icon it’s not shown that way. His hands are flat to show that He placed Himself on the cross willingly. We also see that His face seems to be very peaceful, He’s almost asleep on the cross, His hair is unmessed; and this shows that He was at peace on the cross. He had made His peace with the Father. He had accepted the cup of His suffering and He was in great peace on the cross. We know that physically He was in pain, but His spirit was at peace.

Now the titulus which we see on the icons, the little placard that would say the crime, is abbreviated. Sometimes it says “INBI”, or sometimes it says “INRI”. Usually of course in the Orthodox Church it will say “INBI”, and that’s shorthand. It stands for “Jesus of Nazareth” (the name “Jesus” in Greek starts with an “I”, “Iesous”), “Jesus of Nazareth King of the Jews.” “Jews” also starts with an “I, and the “B” is for the Greek word for “King,” “Basileus.” If it reads, “INRI,” as you sometimes see in the West, it simply represent the same words in Latin. But “king” in Latin is “Rex,” so that’s the reason for the “R”. However, a true Orthodox icon of the Crucifixion will not say either of these things, but will say, “King of Glory,” because that’s what the cross is in the theology of the Church.

So you see that this is not an intentional depiction of a historical event, but an expression of the theological meaning that Christ was truly the king. He called the cross His “glory.” It was the hour of His glory. This is emphasized in the Gospel of John. And even though St. Paul speaks of the cross more as the humility of Christ, even he says in Corinthians 2:8, “If they had known, they would not have crucified the Lord of Glory.” We remember the Resurrection in even the darkest moments of Holy Week—so, we don’t dwell very much upon the suffering of Christ. We know, of course, that He suffered greatly, and we honor Him for this. We say in the most famous hymn of Great and Holy Thursday: “We praise your Passion, O Christ,” but then we continue and say, “show us also Thy glorious Resurrection.” And we say, “Glory to your forbearance, O Lord.” So the cross is the symbol not only of Christ’s glory and His victory over death, but His forbearance, His longsuffering, His supreme love for us… Naturally, I cannot exhaust all of the things that can be said about the Cross. One of my favorite Chrysostom quotes is, “Christ was victorious not by killing, but by dying.”

The fathers on the spiritual meaning of the Crucifixion.

Lastly I would like to end with some beautiful quotations from the Fathers on the spiritual meaning of the Crucifixion, and not so much the historical details.

That Christ conquered through humility, St. Jerome said: “Christ was crucified in order to rule. He conquered the world not in pride, but in humility. He destroyed the devil not by laughing, but by weeping. He did not scourge, but was scourged. He received a blow, but did not give blows. Therefore let us imitate our Lord.”

Now about the humility of the Lord, the humility shown by Him by the death on the cross as the ultimate example for us, St. Augustine said: “The Lord thought fit to signify all the terrifying, harsh, bitter, unbearable things, all the savagery, by the name of the cross. I mean, among the various kinds of death, there is none more unbearable than the cross. Indeed, when the Apostle Paul was drawing the humility of the Lord to our attention, he added this name, the cross, with the most weighty emphasis.”

St. Jerome: “The cross is the key which opened Paradise. The cross of Christ is the key to Paradise, the cross of Christ opened it. Did He not say to you: ‘The Kingdom of Heaven has been enduring violent assault, and the violent are seizing it by force?’”

Now here’s a quotation from St. Augustine that I think is really amazing: “Why do you sign yourself with the cross? If you don’t act the cross, you don’t in fact sign yourself with it. Recognize Christ crucified, recognize His suffering, recognize Him praying for His enemies, recognize Him loving those at whose hands He endured such things and longed to cure them. If you do not recognize Him, repent.” Now what is St. Augustine’s point there? I think it is very, very deep. People were crossing themselves in the early Church. This is not something that was invented later. He’s not the first person to mention the sign of the cross. But he said that the sign of the cross is not simply a prayer or a blessing—that’s the way we usually think of it. But if we sign ourselves with a cross, we’re supposed to behave like the one who was crucified on the cross. Otherwise, when we sign ourselves with it, it’s meaningless. He says we have to “act the cross”; that is, we have to forgive those who harm us, we have to remember that Christ was crucified, remember the fact that He loved even those at whose hands he endured such things. I think it’s a very profound insight.

Here’s another wonderful quote from St. Augustine who compared the impact of St. Peter’s life to that of the Emperor Hadrian; and of course he’s referring to the fact that this has to do with the cross. There is a relationship here to the crucifixion of Christ. He talks about how after the Roman emperors died, they were proclaimed gods and temples were built to them as gods. So here’s what he says, comparing Peter to Hadrian: “In Rome, there can be found the tomb of a fisherman, and also, the temple of an emperor. Peter is there in a tomb, Hadrian is there in a temple. A temple for Hadrian, a memorial chapel for Peter. An emperor comes to Rome; let us see where he hurries off to, where he wishes to kneel: in the emperor’s temple, or in the fisherman’s memorial chapel? Laying aside his diadem, he beats his breast where the fisherman’s body lies. It is on his merits that he reflects, on his crown that he believes, through him that he is eager to reach God; by his prayers he feels and discovers that he is assisted. So there you are: the achievement of the One who is Crucified and scorned on the cross. There you have what He mowed down the nations with. Not with ferocious steel, but with a scorned piece of wood.”

Chrysostom said that when we think about the crucifixion of Christ, we should remember that we should not expect honors in this life. Here’s what he had to say: “Arise, O man, on hearing these things and seeing your Lord driven in fetters from place to place. Have no esteem for the present life. Is it not a strange thing indeed, if Christ has undergone such great sufferings for your sake, whereas you frequently cannot even bear up under harsh words? But He, on the one hand, was spat upon; whereas you adorn yourself with fine apparel and rings. And, if you do not meet with words of approval from all people, you consider life not worth living. Yes, He was insulted, endured jibes and mocking blows against His face, while you wish to receive honor at all times and cannot bear the dishonor received by Christ. Do you not hear Paul saying: ‘Be imitators of me, as I am of Christ’? When someone ridicules you, then remember your Lord, that they bowed the knee to Him in mockery, dishonored Him both in word and in deed, and showed great hypocrisy toward Him. However, not only did he not reciprocate, but even gave back the opposite, namely, gentleness and kindness.”

Now the last one I’m going to share from you from Chrysostom is about how we should not seek victory. Listen to this: “Let us not then everywhere seek victory, nor everywhere shun defeat. There is an occasion when victory brings hurt, but defeat – profit. For instance, as in the case of those who are angry. He that has been very outrageous seems to have prevailed; but he that endured nobly, this man has got the better, and conquered. He who is wronged, and seems to have been conquered, if he has borne it with self-command, this, above all, is the one that has the crown. For never do we overcome by doing wrongfully, but always by suffering wrongfully. Thus also the victory becomes more glorious when the sufferer gets the better of the doer, because thereby it is shown that the victory is of God. God has given you the might to conquer—not by might, but by endurance alone.”

Well I’m so glad that I have these enlightening and inspiring insights from the Fathers to share with you, because I am entirely inadequate to express the depth of this great mystery of the Crucifixion. I beg your forgiveness for my shortcomings, my failings, my errors, my offences, and I wish you all a joyous Resurrection.

Now let’s close with our prayer: “Lord, now let Thy servants depart in peace according to Thy word, for our eyes have seen Thy salvation which Thou hast prepared before the face of all peoples, a light to enlighten the Gentiles and the glory of Thy people Israel.”

Presbytera and Dr. Jeannie Constantinou’s podcasts can be found here.