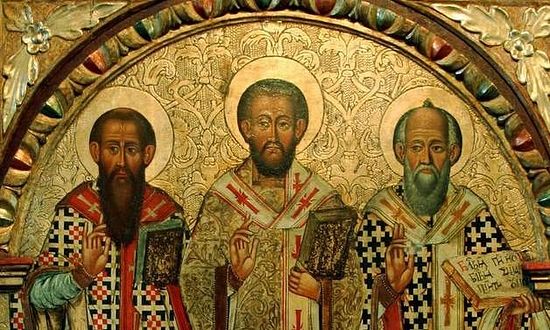

Basil, Gregory, and John are so often remembered together that it’s difficult to think of them separately. However, they, like Peter and Paul, are strikingly opposite in many aspects. Elucidating these contrasts does not destroy, but, on the contrary, underscores the unity which they were given in the Holy Spirit and which has organically entered into the consciousness of the Church.

The first place in this little synaxis of holy hierarchs can be given to Basil. Everything that we can say about Gregory and John, we can say about Basil. They are warriors against heresy—and so is he; they are bright preachers of the Word—and so is he. A courageous spirit, love of solitude, a humble life, a deep comprehension of dogmas—all of this and much more these three fathers have in common. All three come from holy families. Their mothers, fathers, and siblings constitute an entire constellation of personalities remarkable in holiness. But Basil is distinguished by the highest order of self-discipline. Basil is an organizer, which you cannot say about Gregory and John, or at least, not without reservation. Everywhere that Basil went, he left behind a strict hierarchy and order. He, without a doubt, was a charismatic man, but he relied upon Church praxis, not only the strength of personal influence and spiritual gifts. Everywhere Basil the Great brought discipline and statutes, laws and organization—in a word: order. Indeed, things in the Church then were like a battle at night, where everyone hits both enemy and ally, seeing and understanding nothing.

Basil’s mind and intellect allowed him to become a scholar, and his will and strictness were able to make of him a true monk, like Anthony. But he sacrificed all his talents in battle for the sake of the Church. He deeply hid his spiritual meekness to become unshakable, and, at least secretly, like his friend Gregory, he longed for the tranquil life, for the desert and seclusion. Few understand what it means, loving the Scriptures and silence, to sacrifice yourself and jump into the thick of a fight for the Church and its dogmas, having no rest, risking your life, and perishing daily.

John was completely different, and even more distinct from these first two stands Gregory. John is the people’s favorite and leader, but he is outside the system. Bishops did not love him, and not only heretical bishops. The royal court was infuriated by his teachings and denunciations. The Golden-Mouthed[1] leaves behind his name, words, and memory, but no organization, no combat structure. His friends and inner circle fall out of favor and become victims after his expulsion. And this is not a reproach, but emphasizes the dissimilarity, for every soldier in Christ fights as he is able.

But Gregory is a contemplative. He, of course, lives among people and edifies his flock, inasmuch as he bears the highest ecclesiastical office. But he feels the burden of his office, the burden of that which those unworthy of it so eagerly seek. The episcopal omophorion becomes a cause of embitterment for Gregory against Basil. The latter subordinates everything, including friendship, to the interests of the Church, and, in essence, forces his friend to become an archpastor at a difficult time for the Church. As a preacher Gregory does not so much exhort and speak as he sings. It is precisely by the sweet voice of his pronouncements, called by the Church “the shepherd’s pipe,” that people infested with delusions throng to the enclosure of the Church and receive Orthodoxy.

Basil has no free time. Gregory writes poetry at leisure. John interprets the epistles of Paul, and the apostle himself appears to him to clarify difficult passages in his epistles. It’s difficult to find three people more psychologically dissimilar among themselves.

* * *

The conflict that brought the memory of the Three Holy Hierarchs together is quite understandable. People are capable of turning all the most holy things into something to bicker and dispute about. The Corinthians argued, saying, I am of Paul … I am of Apollos (1 Cor. 3:4). Then Christians started to debate about which of these three is the greatest and most glorious. The problem is that, when you look at each of them, each could, undoubtedly, be awarded the supremacy. Examine the life of Basil (and each of us ought to do so), penetrate into it, and you will exclaim: “Great is Basil! Who among the saints is like unto him?!” But then begin to consider the image of John, and you will soon say with wonderment: “There is none like John!” If you read carefully the words of Gregory and in silence contemplate the humble features of this possessor of the heavenly mind, then you will forget everyone you praised before, saying: “Pray unto God for me, wondrous Gregory!” There is no greatest among them, precisely because they are different. None is equal to the second Theologian[2] in beauty and precision of word. And in zeal for the glory of God, none can stand with John Chrysostom, except, perhaps, Elijah the Tishbite. Basil is not just a warrior, and ascetic, and sage, and chief of monks, he is also a general, able to assemble a host of disparate soldiers and turn them into an army. All three are great, and great in different ways.

* * *

The Church needs organizers in every age, and fiery orators, and quiet contemplatives. Woe to the Church and the people of God if one of these three is not with them in any age. Thrice woe to the Church if there are none of them! Then fierce ailments will increase and multiply for the sake of a conventional and comely appearance, and there will be no one to cure them.

Every man placed by God in sacred orders must test himself as to which of these three talents more corresponds to his spiritual storehouse and experience. There is no pastor for whom none of these are relevant in any way. But the union of all three gifts in one person is nigh on impossible!

Preacher, organizer, secluded contemplative.

Calmer of the human sea, son of battle and son of prayerful silence.

One of the three.

* * *

If someone commands others, administrates, manages, let him look at the image of Basil the Great. He must not only command, pointing out what others need to do, but he must also stockpile all sorts of knowledge, as did Basil. He must love the fasts and books, and he must gather his strength in solitude to battle for Truth among the multitudes.

If someone preaches in season and out of season, as the apostle Paul commanded, let him flee from meals full of idle talk and kowtowing before the rich, in the image of the Golden-Mouthed. Let him unite to his reading and homilies the fervent serving of the Liturgy and an abundance of almsgiving, after the example of the great fathers, and may he sacrifice everything that his mouth might become the mouth of the Word.

If someone loves solitude, loves long prayers, and with reluctance pulls his mind away from heaven for the sake of earthly matters, let him look at Gregory—he who, as much as it caused him to suffer, left the desert and took up the cathedra when the Church demanded it—he who neglected himself for the sake of the common good and went to sound forth his homilies with silver trumpets, to fell the thick walls of Jericho.

Every man bearing the linen ephod[3] should have at least one of these traits, at least in the most modest of amounts. Refreshing this truth in our minds just might be the main purpose of the Church’s joint veneration of Basil, Gregory, and John.